ITE is crucial to creating a skilled, passionate teaching workforce that can meet the needs of all learners. As such, there has been considerable focus on increasing the quality of teacher education systems, both nationally and internationally.

The teaching workforce is a national asset. Teachers play a significant role in shaping student outcomes (Hattie, 2009), which are an important predictor of economic growth (Hanushek & Wößmann, 2007). Public interest in teacher education

is driven by demand for skilled, effective teachers. This interest is reflected in the numerous government investigations and reports surrounding teacher education that have taken place in recent decades (Aspland, 2006).

Teacher education has changed considerably over the last decade, and while some argue for further new, innovative approaches to ITE (Yeigh & Lynch, 2017), many improvements have already occurred. With changes and updates occurring regularly, teacher

education today looks very different to what many teachers experienced when they were educated.

While the average age of teachers in Australia is 42 years old, 30% of teachers are aged above 50 years. This means that the majority of teachers have been educated through ITE programs that no longer exist or have changed substantially. In Australia,

teacher education has undergone significant transformation, repositioning the delivery of programs from teacher training colleges to higher education institutions and aligning programs directly with national professional standards[1] (Teacher Standards). So, what does a modern ITE course look like? What are the requirements to entry? How have course requirements changed? And how are pre-service teachers assessed before

they complete their education and enter Australian schools?

Nationally agreed span Standards and Procedures[2] govern the accreditation of ITE programs in Australia; ensuring ITE students are receiving consistent, quality training. Prior to their introduction, jurisdictions

and providers worked together to ensure that programs met jurisdictional accreditation standards. ITE providers are encouraged to be innovative in the delivery of programs to meet the diverse needs of students and the profession. Crucially, providers

continue to play an important role in supporting and implementing best practice in teacher education. National Guidelines[3] complement the Standards and Procedures, supporting providers to prepare

and submit evidence to gain accreditation, and assisting accreditation panels to make judgements about the evidence provided.

In order to further strengthen ITE programs to better ensure new teachers have the right mix of academic and practical skills needed for the classroom, the Teacher Educational Ministerial Advisory Group (TEMAG) was established to advise the Australian

Government on teacher training reform (Australian Government, 2014). The issues paper released by TEMAG, Action Now: Classroom[4] Ready Teachers, and the subsequent Australian Government response

highlighted the following key reform areas:

- Selection: comprehensive and transparent selection processes to ensure that students possess academic and non-academic skills

- Quality assurance: ensuring the Accreditation of initial education programs in Australia – Standards and procedures are being effectively and consistently applied

- Robust assessment: all pre-service teachers must meet the Graduate Teacher Standards prior to graduation through a rigorous teaching performance assessment

- Induction: ensuring that all early career teachers have access to nationally consistent, effective, high-quality induction processes

- Professional experience: all pre-service teachers have access to effective professional experience placements

- National research and workforce planning: development of a national data set on initial teacher education and the teacher workforce (Australian Government, 2015).

This Spotlight outlines what a teaching degree looks like for undergraduate and postgraduate students today. It also explores different pathways into teaching qualifications that are available to potential students that aim to increase the

diversity and experience of teaching candidates and the teaching workforce. The reforms introduced over the last decade seek to ensure the teaching workforce is equipped with nationally recognised skills and experience, for their very first day

in the classroom and beyond.

There are multiple ways for applicants to enter ITE programs in Australia. The variety of entry options reflects the broad range of skills teachers need to succeed in the classroom (OECD, 2019). Selection processes are detailed in the Standards and Procedures.

ITE providers[5] are required to:

- set both academic and non-academic criteria for the selection of entrants to ITE programs

- describe in detail the rationale for their approach, the selection mechanisms utilised, threshold entry applied, and any exemptions used

- make publicly available all information necessary to ensure transparent and justifiable selection processes for entry into ITE programs, including student cohort data.

Selection into ITE programs requires both academic and non-academic criteria to be met.

Students who commence on the basis of ATAR only make up a small proportion (18%) of total ITE commencements.

ITE continues to be accessible for a diverse range of students.

Comprehensive screening of potential students helps to ensure only the most suitable candidates are selected to enter the profession. This helps to create a cohort of skilled graduates that are ready to teach.

Although the majority of commencements enter via non-secondary education pathways, ATAR[6] remains one of the most significant topics in public discourse surrounding ITE. However, admission decisions are

increasingly being made on a range of factors other than ATAR (Pilcher & Torii, 2018). In addition to higher education, many students enter teaching qualifications via a vocational education or training program (11%), a mature entry pathway

(3%) or another basis of admission (11%). Secondary education entrants make up a large proportion (26%), but not the majority of total entrants. Additionally, more than a third (34%) of secondary entrants are selected on factors outside of ATAR

(AITSL, 2019). Overall, the variety of admission pathways available to teacher education students helps to ensure a diversity of entrants are admitted to ITE programs, helping to create a more diverse and representative teaching workforce.

Academic based selection

Students who are selected into ITE programs now must meet both academic and non-academic selection requirements. Academically, students should possess literacy and numeracy levels broadly equivalent to the top 30% of the population. If they do not

possess these skills upon entry in a course, they must do so upon exiting (AITSL, 2018). Students’ literacy and numeracy skills are assessed before they graduate via the Literacy and Numeracy Test for Initial Teacher Education Students (LANTITE).

Applicants can access ITE programs through a range of entry pathways. Around half (49%) of all commencements enter via a higher education pathway. A large proportion of these students enter a postgraduate program (30% of all commencements). Entrants

into postgraduate programs are required to have one of the following:

- a discipline-specific bachelor’s degree

- an equivalent qualification relevant to the Australian Curriculum

- another recognised qualification.

Secondary school leavers make up only 26% of total commencements into ITE programs and a significant proportion of this cohort (32% in 2017) commenced without a reported ATAR (AITSL, 2019). This proportion may include, but is not limited to, students

who accepted an early offer or students who have commenced an ITE program at least one year after completing secondary school, for example, after taking a gap year (AITSL, 2019).

Students entering an ITE program with a low ATAR is frequently reported by the media. Despite the prominence of this message, when commencements based on ATAR are measured against the total ITE commencements the emphasis placed on ATAR seems misplaced.

In 2017, those entering with an ATAR of less than 70 made up 6% of commencements (AITSL, 2019).

The ATAR of students whose education may have been disadvantaged for various reasons is ‘adjusted’ based on a series of indicators, which must be described by the ITE provider for transparency reasons, but these adjustments are not unique

to teacher education. Adjustment factors can include:

- Recognition as an Indigenous Australian

- Non-English speaking background

- Disadvantaged financial background

- Disability or medical condition

- Difficult circumstances

- School-based adjustments

The 70 ATAR cut-off applies after these adjustment factors have been used to modify the initial ATAR. This is important so students are not discriminated against when being selected. It is crucial that pre-service teachers are representative of the

Australian population, including in terms of regionality and rurality, as when these teachers graduate, they are more likely to fill roles within their community, eventually increasing student outcomes and decreasing staff turnover (Cuervo and

Acquaro, 2018).

Advantages and disadvantages of ATAR (points summarised from Pilcher & Torii, 2018)

Advantages

- Transparent process

- A fair way for universities to compare students from a wide range of schools

- A widely used measure of students’ overall academic performance

- Facilitates efficient decisions surrounding admission within a consistent timeframe

Disadvantages

- Only provides a broad snapshot of student academic ability

- Masks the strengths and weaknesses of students in particular subjects

- Relative rank in that ATAR score will depend on the strength of the cohort in any given year

- Unable to qualify small differences in score meaningfully. For example, it is unclear what the relationship is between an ATAR score difference and student ability, particularly when scores are close together, i.e. 69.95 and 70.05.

Non-academic selection

Students are not admitted to ITE programs based on their academic abilities alone. Providers are required to identify and admit candidates who can demonstrate they have the necessary non-academic capabilities that will enable them to successfully

graduate as classroom-ready teachers (AITSL, 2018). The key non-academic capabilities associated with successful teaching include:

- a motivation to teach

- strong interpersonal and communication skills

- a willingness to learn

- resilience

- self-efficacy

- conscientiousness

- organisational and planning skills.

Tools to determine the suitability of a candidate’s non-academic capabilities fall under three categories: written assessments; interviews; and online assessments. In most instances, the selection criteria generally focus on motivation and suitability

for the teaching profession as well as leadership experience.

Written assessments

Most providers require a written statement, usually either a personal statement or responses to specific questions. Several providers require written statements focussing on motivation and suitability to teach and involvement in personal learning

and leadership activities. These statements range from 400 to 1000 words.

Interview assessments

ITE providers may elect to undertake interviews to assess against non-academic criteria. These are largely similar to written assessments and generally assess motivations to teach, willingness to learn and leadership capability based on previous experiences.

Online assessments

Providers may also opt to implement online assessment tools. These tools vary in functionality with some acting as digital replacements for written tools. Other tools are more interactive, creating an immersive experience for prospective students.

Several providers utilise online tests that determines personal and professional attributes. Like the other modes of assessment, these online tools generally aim to assess motivations and suitability for teaching.

Diversity of platforms used to assess non-academic capabilities

CASPer

CASPer is a Situational Judgement Test (SJT) that presents prospective ITE students with hypothetical scenarios identifying how individuals behave in certain situations. The primary purpose of these tests is to assess applicants for non-academic

attributes and people skills. Universities across Victoria utilise this assessment tool including Australian Catholic University, Deakin University, Federation University, La Trobe University, Monash University, RMIT University, Swinburne

University of Technology and Victoria University.

SimLabTM

SimLabTM is an immersive platform that offers prospective students a mixed reality learning environment with student avatars responding in real time. The purpose of this assessment is to assess language and discourse, improvisation, rapport building

and teaching self-efficacy. Murdoch Univeristy utilises this platform.

Crick Learning for Resilient Agency (CLARA)

Melbourne Polytechnic utilises this online assessment tool to inform interview discussions with potential entrants. The tool comprises a 40-item web survey, the results of which generate a “Learning Power” profile based on eight dimensions:

curiosity, creativity, sense making, belonging, collaboration, hope and optimism, mindful agency and openness to change.

Teacher Capability Assessment Tool (TCAT)

The University of Melbourne requires potential entrants to complete the TCAT prior to applying. The web-based tool comprises five modules with open response and multiple choice questions. The modules cover potential entrants’ previous experience

and motivations to teach and include questions on literacy and numeracy skills, other abilities and disposition.

Non-Academic Capability Assessment Tool (NACAT)

The University of Tasmania’s NACAT is made up of a 1000-word personal statement as well as some multiple choice questions.

Employment-based pathways

There are a variety of employment-based pathways into teacher education that allow students to gain professional teaching experience and study at the same time. They also aim to attract teaching candidates with diverse experiences and from different

professional backgrounds. Some of these pathways are part of the Australian Government’s High Achieving Teachers Program, which supports alternative pathways into teaching for high-achieving individuals who are committed to pursuing

a career in teaching.

Nexus program at La Trobe University

The Nexus program aims to graduate high-achieving teachers who will take up teaching positions in socio-culturally diverse, low socio-economic schools in Melbourne and regional areas across Victoria. Students are required to complete their postgraduate

qualification – a Master of Teaching (secondary) – while working in schools as an education support worker for the first nine months. They then take on full teaching responsibilities for the following year. This program is also supported

by the Australian Government’s High Achieving Teachers Program. It commenced with a cohort of 40 students in 2020 and aims to enrol another 40 students in 2021.

Melbourne Graduate School of Education’s Master of Teaching (secondary) internship

This program places students in vacancies that are difficult to fill and focuses on the recruitment of graduates from backgrounds that reflect existing teacher employment demands. Interning students are placed in government secondary schools, often

in remote locations that are facing staffing shortages, and complete their postgraduate qualification over two years. The program is supported by the Victorian Department of Education and Training.

Teach for Australia

This program requires students to undertake a teaching internship while completing a Master of Teaching (Professional Practice) at the Australian Catholic University. It aims to place high-achieving graduates, professionals and individuals looking

for a career change with subject matter expertise in government schools, often serving low socio-economic communities. Participants begin teaching at the beginning of term one and complete their postgraduate qualification over their two-year teaching

placement. The program currently operates in the ACT, the Northern Territory, Tasmania, Victoria and Western Australia and is supported by the Australian Government’s High Achieving Teachers Program. Since 2010, the program has

placed 831 teachers across 182 schools.

Commencing ITE students

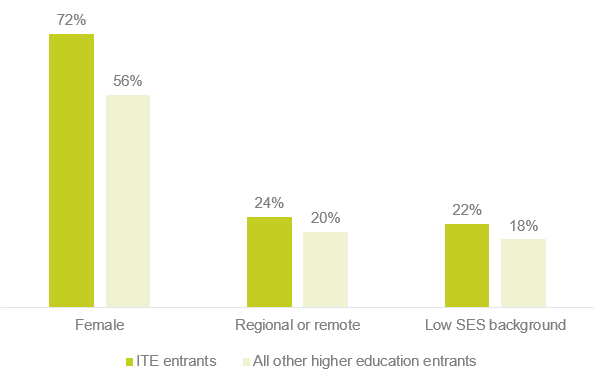

Commencements into ITE has remained relatively consistent since 2012, with approximately 30,000 students beginning yearly. ITE students are considerably more likely to be female compared to all other higher education entrants (ITE: 72%; all other

higher education: 56%). Many ITE students come from a regional or remote location (ITE: 24%; all other higher education: 20%) and may be from low socioeconomic status (SES) backgrounds (ITE: 22%; all other higher education: 18% - refer to Figure

1) (AITSL, 2019). Approximately 2% of ITE students are Indigenous, which is consistent with levels of enrolment by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people in other areas of tertiary study, but smaller than the school student population (5.7%)

(AITSL, n.d.).

Figure 1: Demographic characteristics of commencing ITE students compared to all other higher education entrants (2017)

ITE students can study on campus, online or a combination of the two (multimodal). The proportion of ITE students commencing through an internal (i.e. on campus) mode of attendance has declined from 75% of all commencing students in 2008, to 60% in

2017. Now, one in four ITE students commence as part of an online ITE program. Multi-modal commencements have been steadily rising since 2010 (10% in 2010; 15% in 2017) (AITSL, 2019).

Whilst rigorous entry requirements ensure that only suitable candidates are admitted into teacher education programs; the quality of pre-service teachers also depends on the quality of their program, the content delivered, professional experience

opportunities and the pre-service teachers commitment to learn and develop. ITE programs are designed to produce highly skilled teaching candidates who are ready for their first day in the classroom and beyond. Across the country, whether students

are studying on campus, online or a combination of the two, providers are responsible for ensuring that teaching candidates meet both academic and non-academic standards. The reforms outlined below have been implemented to increase the quality

of programs and maintain consistency across the country.

Quick Link

For more information regarding the challenges of delivering ITE programs in the digital landscape see the ITE Online Spotlight

Shift in focus to Masters qualifications

One significant change in recent years has been the phasing out of one-year programs and increased emphasis on postgraduate teaching qualifications (O’Donoghue, 2018). Previously, one-year diplomas were available to graduate students from any

degree. Now, all postgraduate teacher education programs must be a minimum of two years or equivalent, often a two-year Master of Teaching. An ITE graduate must, therefore, have undertaken a four-year bachelor’s degree or a bachelor’s

degree plus a two-year master’s degree to apply for teacher registration. These requirements help to ensure that all graduate teachers have been taught and assessed against the graduate level of the Teacher Standards and have been given the opportunity to gain practical classroom experience. Commencements into Masters’ level programs have increased from 8% in 2008 to 21% in 2017 (AITSL, 2019).

Professional experience

A key component of teacher education is comprehensive professional experience for pre-service teachers. ITE providers are required to have formal partnerships with schools in order to facilitate quality professional experience (i.e. placements) for

teaching candidates and for trained mentors to guide candidates through these experiences. These are usually undertaken within schools or early childhood settings. This requirement was formalised in 2011 with the introduction of the Standards and Procedures and reforms in this area are ongoing. All accredited programs must include professional experience which fulfils the following requirements:

- is relevant to a classroom environment

- includes no fewer than 80 days in undergraduate and double-degree teacher education programs and no fewer than 60 days in graduate-entry programs

- consists of supervised and assessed teaching practice undertaken over a substantial and sustained period that is mostly in Australia and mostly in a recognised school setting

- is as diverse as practicable

- provides opportunities for pre-service teachers to observe and participate purposefully in a school/site as early as practicable in a program (AITSL, 2018).

“Every practicum I have been on was inspiring and justified my decision to take on a new career.”

– Pre-service teacher (Varadharajan, Carter, Buchanan, & Schuck, 2020).

Content requirements, evaluation and reporting

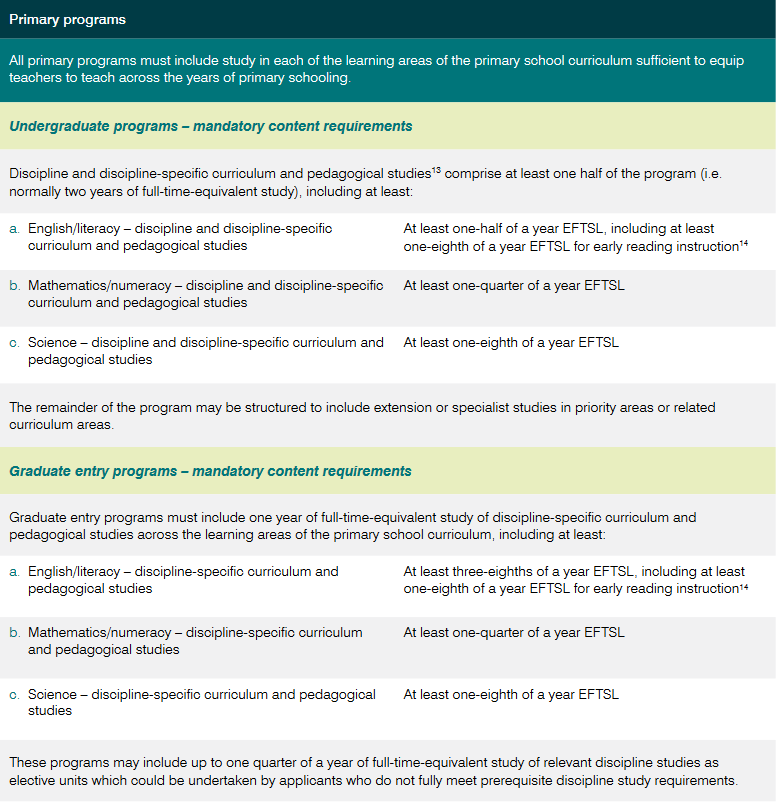

Accredited ITE courses include mandatory content requirements that are appropriate for the program setting (primary or secondary) and the level of qualification (undergraduate or postgraduate) as outlined in Figure 2. These programs are tailored in

order to give teaching candidates opportunities to learn, practice and demonstrate the Graduate Teacher Standards outlined in the Australian Professional Standards for Teachers.

Figure 2: Minimum content requirements (AITSL, 2019, p17).

Not only are ITE programs required to meet national standards for content and provision of professional experience, but providers are also required to regularly analyse, report on and evaluate their programs to inform design and delivery improvements.

In attaining and maintaining accreditation for ITE programs, at a minimum, providers must:

- develop a plan to evaluate and demonstrate outcomes for each program in relation to pre-service teacher performance and graduate outcomes (for example teaching performance assessments, pre-service teacher satisfaction surveys, teacher registration

data for graduates or employer perceptions of graduates)

- report on strengths, program changes and planned improvements and

- report regularly to teacher regulatory authorities in their state or territory (AITSL, 2018).

The selection standards and program requirements have been implemented to ensure teaching graduates meet the requirements set out in the Standards and Procedures and the Graduate Teacher Standards. The Literacy and Numeracy Test for Initial Teacher

Education Students (LANTITE) and teaching performance assessment (TPA) are tools used in assessing if these standards are being met by students. To graduate, ITE students must successfully complete and pass both LANTITE and a TPA as well as any

other assessments that satisfy the Graduate level of the Teacher Standards.

Prior to completion students are required to successfully complete LANTITE, a measure of literacy and numeracy

The LANTITE test standard is equivalent to the top 30% of the Australian adult population

Students must successfully complete TPAs demonstrating their teaching practice against the Graduate Teacher Standards

Diversity amongst ITE students completing their program remains high

The Literacy and Numeracy Test for Initial Teacher Education Students (LANTITE)

In 2015, all education ministers agreed an assessment would be used to demonstrate students have achieved a level of literacy and numeracy within the top 30% of the population. Following this, LANTITE[7] was developed and has been in place since 1 July 2016 (Australian Government Department of Education, 2020).

LANTITE (ACER, 2020)

Test duration

The test consists of 130 questions and candidates are given four hours to complete. All the questions are in either selected responses (for example, multiple-choice) or short answer formats. The test is comprised of two components, literacy and

numeracy.

- For literacy, the test has one section comprising 65 questions. Students are given 120 minutes to complete this section.

- For numeracy, the test has two sections. The total available time is 120 minutes. Section one consists of 52 questions and a calculator is permitted while section two consists of 13 questions but a calculator is not permitted.

Test content

The literacy component of the test measures two key areas;

- Reading text, including procedural, regulatory and technical, descriptive, informative and persuasive and narrative texts

- Technical writing skills, including syntax and grammar, spelling, word usage and text organisation

The numeracy component test measures three content areas;

- Numbers and algebra

- Statistics and probability

- Measurement and geometry

Test timing and conditions

There are four fortnightly test window opportunities per year. Candidates attend a central location and undertake the tests online. Tests are delivered via a highly secure online testing platform. Specific arrangements can be made for the test

to be taken remotely.

Teaching Performance Assessments

All pre-service teachers are required to successfully complete a Teaching Performance Assessment (TPA). TPAs are a culminative assessment and provide summative evidence of graduate teacher competence. Candidates need to demonstrate what they want

students to learn, how they will facilitate this learning and how they will know if students have achieved this learning. Overall, TPAs give candidates the opportunity to demonstrate their impact on student learning.

TPAs are required to take place in a classroom environment so ITE candidates can demonstrate a range of authentic teaching practices. The TPA is a requirement of successful program completion and must be completed during the student’s final

year. Where possible, it should be included in the final professional experience placement or internship. TPAs are assessed by the training provider and not a supervising teacher or mentor.

In completing a TPA, a pre-service teacher illustrates their skills, knowledge and teaching practices through evidence of their performance across a sequence of lessons that are aligned to the Graduate level of the Teacher Standards. This could be

through:

- classroom observation

- lesson plans

- assessment strategies and feedback

- samples of student work

- observation of notes and reflection (Teaching performance assessment: Program Standard 1.2 Fact Sheet, 2020).

Rigorous assessment of pre-service teachers is a critical element that provides students, families and schools with confidence that graduates from Australian ITE programs are effectively prepared to enter the classroom and are well-equipped to have

a positive impact on student learning from day one. Now that TPAs are an established component of ITE, jurisdictions and providers are continuing to work together to ensure fidelity in implementation and the ongoing use of data to inform program

developments and improvements.

Key features of Teaching Performance Assessments

In completing a Teaching Performance Assessment (TPA), ITE students will draw evidence from their own practices to demonstrate:

- what they want students to learn

- how they will facilitate this learning

- how they will know if students have achieved this learning.

Students must complete a TPA in their final year of study and it must take place in a classroom environment. A TPA must also:

- be a reflection of classroom teaching practice including the elements of planning, teaching, assessing and reflecting

- be a valid assessment that clearly assesses the content of the Graduate level of the Teacher Standards

- have measurable and justifiable achievement criteria that clearly distinguish between meeting and not meeting the standards

- be a reliable assessment that includes processes that ensure consistent scoring between assessors

- include a moderation process that supports consistent decision making against criteria.

Graduates

Approximately 18,000 students successfully completed an ITE program every year between 2013 and 2017. Completion rates are consistently higher for postgraduate students (78%) when compared to undergraduate students (51%) (AITSL, 2019); however as

there are more undergraduates enrolled in ITE (79%) compared to postgraduates (16%), a larger proportion of new teachers graduate with an undergraduate degree (61%) than a post-graduate degree (39%) (Figure 3) (AITSL, 2020). Of all completions

in 2017, the greatest proportion of students completed a secondary education program (40%), followed by primary (36%) and early childhood (13%) education programs, 10% completed a mixed program and 1% completed an ‘education other’

ITE program (AITSL, 2020).

Figure 3: Course demographics of students completing ITE in 2017 (ITE Pipeline report)

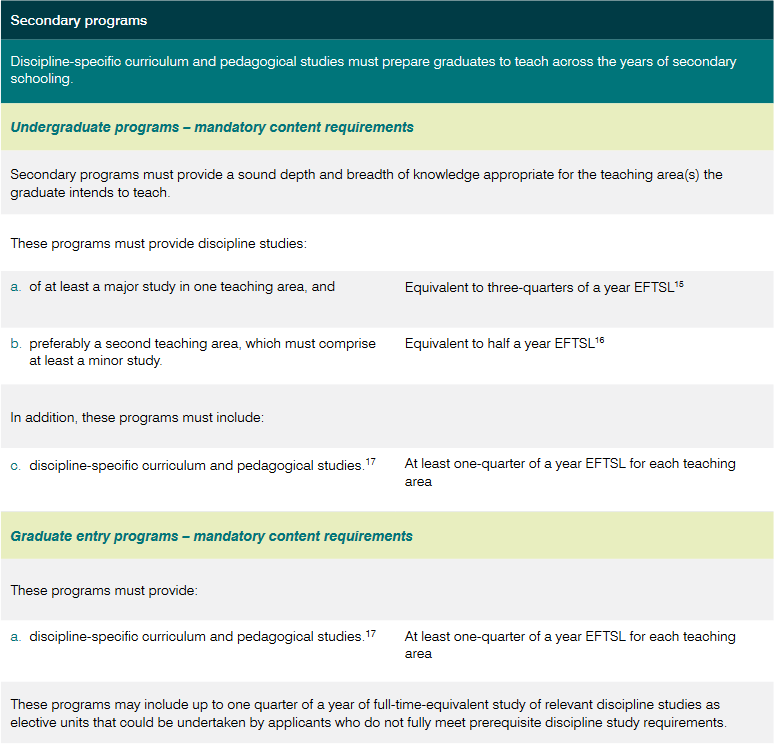

ITE programs continue to be accessed more by students from low and medium socioeconomic status backgrounds compared with other higher education programs. Similarly, the proportion of Indigenous ITE students completing their program is higher than

in other higher education programs. In contrast, a higher proportion of students from non-English-speaking backgrounds complete other higher education programs when compared to ITE programs (Figure 4).

Figure 4: Program completion demographics of students completing ITE in 2017

Student outcomes and experience

Unit or subject completion can be measured using success rates (AITSL, 2019). Success rates are calculated as the sum of all units of study passed by students in a given year, divided by the sum of all units of study attempted (passed + failed + withdrawn)

by those students. Data indicates that success rates within ITE programs have remained consistently high. In fact, teacher education students’ success rates have remained higher than other higher education programs over time. In 2017, the

success rate for ITE students was 90% compared to 88% for all other higher education students (AITSL, 2019). There has been little fluctuation in this data over the past decade.

The Quality Indicators for Learning and Teaching (QILT) are a suite of Australian Government endorsed surveys for higher education, which cover the student life cycle from commencement to employment. One component of this survey focuses on the

student experience[8]. The findings from this survey indicate student experience varies little between ITE programs and other higher education programs. The overall quality of educational experience was high amongst undergraduate (78%) and

postgraduate (75%) ITE students in 2019, similar to the overall educational experience of other undergraduate (78%) and postgraduate (76%) higher education students (Social Research Centre, 2020). This data has changed little over recent years.

The OECD’s Teaching and Learning International Survey (TALIS[9]), gives insights into how Australian teachers’ study experiences compare globally. TALIS gives teachers and principals an opportunity

to share their experiences of teaching practice, professional development, recognition and leadership. In the most recent report, Australia performed well in comparison to other highly regarded countries like Finland and Japan on the metrics preparedness

to teach content (Australia: 68%, Finland: 66%, Japan: 45%) and pedagogy (Australia: 63%, Finland: 62%, Japan: 44%). However, Australia fell short of the OECD average on both measures (Content: 80%, Pedagogy: 71%) (OECD, 2019).

Conversely, the range and depth of Australian ITE programs compared favourably to most other OECD countries: 82% of teachers reported content, pedagogy and classroom practice in some or all subjects was taught in their teacher training, while the

OECD average was 79% (OECD, 2019). This suggests that while Australian ITE programs are on par with other OCED countries, there is room for improvement as programs continue to strive for national consistency and high-quality training for Australia’s

future teachers.

“It will never go to waste [the teaching qualification] – I am definitely a lot more confident in my dealings with kids, so while it cost me time and money - I gained a lot of other things that will help me so much in the future.”

– Pre-service teacher (Plunkett & Dyson, 2011).

ITE today ensures teaching graduates are well prepared with a combination of academic knowledge and classroom teaching skills. ITE graduates are more likely to find that their qualification prepared them for employment (undergraduate: 86%; postgraduate:

81%) in comparison to graduates from all higher education programs (non-ITE programs) (undergraduate: 69%; postgraduate: 75%) (AITSL, 2019).

A recent study also found that a cohort of graduate teachers felt well-prepared for the realities of classroom teaching at the conclusion of their teaching qualification. Crucial to this confidence was the ongoing integration of theory and practice

throughout their degree, including the development of skills and specific resources they could use in their classroom practice and the opportunity to reflect on past practical experiences (Green, Eady, & Andersen, 2018). Graduates in the study

cohort said they were “connected to real-world situations and shown strategies and resources for use in [their] classrooms” and commented that “[it is] very helpful… to be prepared for the classroom practically rather than just theoretically” (Green, Eady, & Andersen, 2018).

A landmark study has highlighted areas for improvement; graduate teachers across Australia reported they felt less well prepared for classroom management, professional engagement with parents/carers and the community, assessment and the provision

of feedback and reporting on student learning, and teaching culturally, linguistically and socio-economically diverse learners, and better prepared for pedagogy, professional ethics and engagement with ongoing professional learning (Deakin University,

2015).

Having more overall confidence in preparedness to teach may explain why ITE graduates report such high levels of satisfaction with their program. In turn, employers also recognise the quality of ITE programs, with a higher proportion of employers

being satisfied with ITE graduates’ performance (87%) in comparison to graduates from all higher education programs (83%) (AITSL, 2019).

Employment outcomes

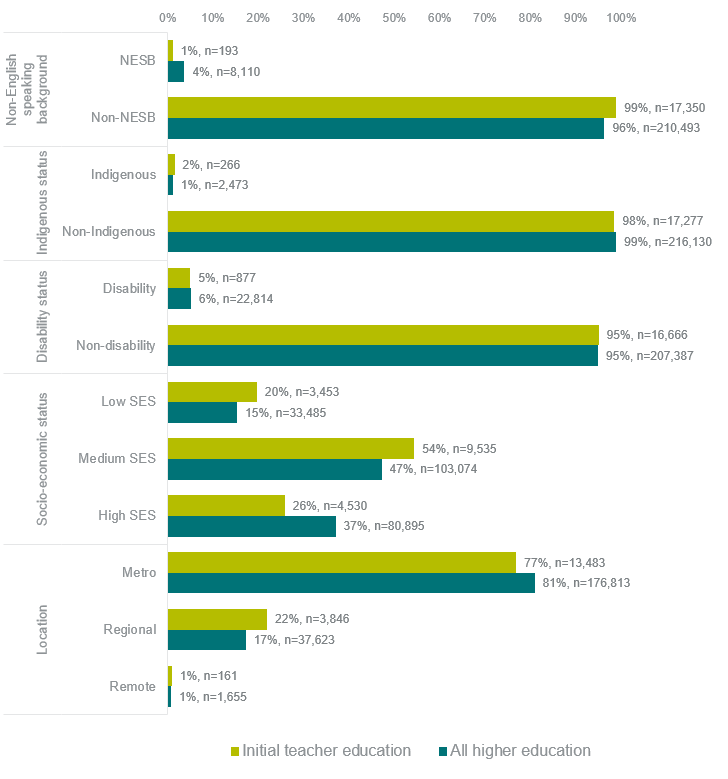

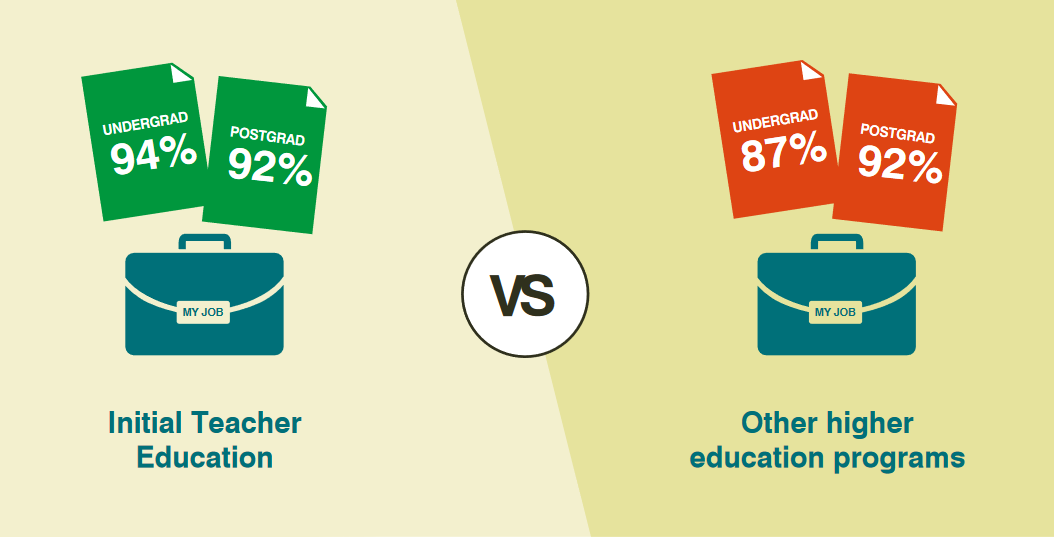

ITE graduates are generally more likely to be employed within one year of graduation compared to graduates from other higher education programs (Figure 5).

Figure 5: Overall employment and in-school employment rates for graduates from ITE and other higher education programs (AITSL, ITE data report 2019)

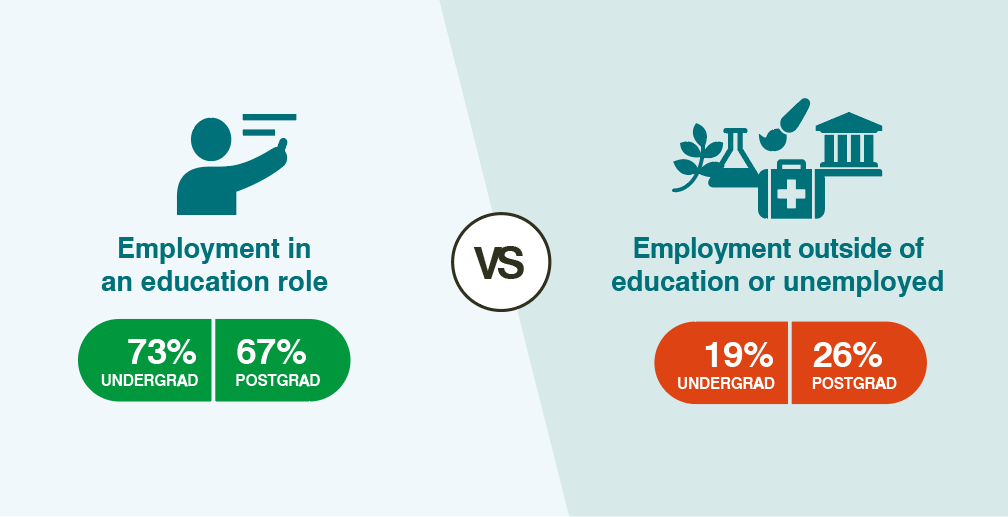

Unsurprisingly, most ITE graduates become employed in education roles. In 2017, more than two thirds (71%) of graduates reported they were employed full-time in schools or early childhood settings, Figure 6 (AITSL, 2020).

Figure 6: Overall employment and in-school employment rates for graduates from ITE and other higher education programs (AITSL, ITE Pipeline report)

School-based employers are pleased with the quality of ITE graduates. The vast majority (93%) of principals felt graduates entering their school were ‘well’ or ‘very well’ prepared for employment (AITSL, 2019). Most ITE graduates

(87%) employed in schools or early childhood education considered their qualification to be important to be able to do their current job (AITSL, 2020).

ITE has changed significantly in recent years. Over the last decade, various reforms have introduced national standards that all teacher education programs must meet. These standards are helping to guarantee Australia has a workforce of well-qualified

and consistently trained teachers who are ready to face the demands of classroom teaching from day one. At the same time, a wider variety of pathways into teaching have become available to prospective teachers, thereby increasing the diversity

and experience of our teaching workforce.

Mechanisms like the TPA and LANTITE have been introduced to provide confidence that graduates are equipped with the skills and knowledge required to be effective teachers. Simultaneously, the quality of teacher education programs is increasing as

providers are required to ensure students receive professional experience opportunities and meet minimum content requirements. Providers are also required to constantly review and evaluate programs to maintain accreditation.

The full impact of these reforms will take several years to realise as pre-service teachers progress through their studies and move into the classroom. The Australian Teacher Workforce Data (ATWD) project will help capture some of these impacts. Overall,

recent changes to ITE will play a significant role in ensuring that Australian teachers are equipped with the knowledge and skills they need to be effective teachers.

The ATWD initiative is a national project which aims to unite and connect ITE data and teacher workforce data from around Australia. It provides nationally consistent data on trends in teacher education, the teacher supply pipeline and the teacher

workforce in Australia. The initiative will help inform national policy on how to better support the profession and strengthen the impact teachers have on their students’ lives.

Learn more about the ATWD. View the ATWD’s first report, National Initial Teacher Education Pipeline.

Footnotes

- Particularly the Graduate Teacher Standards of the Australian Professional Standards for Teachers.

- Accreditation of initial education programs in Australia – Standards and Procedures

set out the requirements that an initial teacher education program must meet to be nationally accredited. They are designed to ensure that all graduates of initial teacher education meet the Australian Professional Standards for Teachers at the Graduate career stage. The Accreditation Standards and Procedures were initially developed in 2011 and revised in 2015, with further updates made in 2018 and 2019.

- Guidelines for the accreditation of initial teacher education programs in Australia were published in 2016 and a revised version will be made available on the AITSL website in early 2021.

- The terms ‘classroom’ and ‘school’ are used throughout this Spotlight and may also include other educational settings where learning occurs.

- Higher education providers (predominantly universities, who make up 37 of the 47 providers) deliver ITE programs in Australia

- The Australian Tertiary Admissions Rank (ATAR) is a number between 0.00 and 99.95 that indicates a student's position relative to all students in their age group. For example, an ATAR of 75 indicates a student is 25% from the top of their age group. The rank is used by institutions to compare students’ achievement.

- LANTITE was validated with reference to the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) Programme for the International Assessment of Adult Competencies and teacher educators from higher educator providers were consulted during its development.

- Data on graduate satisfaction and employment outcomes are captured through the Graduate Outcomes Survey and the Graduate Outcomes Survey – Longitudinal, while employer perceptions of recent graduates are captured through the Employer Satisfaction Survey. These surveys, along with the Student Experience Survey, comprise the suite of QILT surveys.

- The TALIS report is part of a suite of products produced by the OECD.

AITSL. (n.d.). Spotlight - Diversity in school leadership. Retrieved from https://www.aitsl.edu.au/docs/default-source/research-evidence/spotlight/spotlight-diversity-in-school-leadership.pdf?sfvrsn=93effa3c_6AITSL. (2018). Accreditation of initial teacher education programs in Australia - Standards and Procedures. Melbourne: AITSL.

AITSL. (2019). ITE Data Report 2019. Melbourne: AITSL.

AITSL, 2020. National Initial Teacher Education Pipeline. Melbourne: AITSL.

ACER. (2020, January 7). Literacy and Numeracy Test for Initial Teacher Education Students. Retrieved from ACER: https://teacheredtest.acer.edu.au/

Aspland, T. (2006). Changing Patterns of Teacher Education in Australia. Education and Research Perspectives, 140.

Australian Government. (2014). Action now: Classroom ready teachers. Teacher Education Ministerial Advisory Group. Canberra: Australian Government.

Australian Government. (2015). Action Now: Classroom Ready Teachers: Australian Government Response. Canberra: Australian Government.

Australian Government Department of Education. (2020, 01 09). Literacy and Numeracy Test for Initial Teacher Education Students. Retrieved from Australian Government Department of Education: https://www.education.gov.au/literacy-and-numeracy-test-initial-teacher-education-students

Cuervo, H., & Acquaro, D. (2018) The problem with staffing rural schools. Retrieved from https://pursuit.unimelb.edu.au/articles/the-problem-with-staffing-rural-schools

Deakin University. (2015). Studying the Effectiveness of Teacher Education - Final Report. Retrieved from http://www.setearc.com.au/wp-content/uploads/2013/08/SETE_report_FINAL_30.11.152.pdf

Green, C., Eady, M., Andersen, P. (2018). Preparing quality teachers. Teaching & Learning Inquiry 6,(1), pp. 104-125.

Hanushek, E. A., & Wößmann, L. (2007). The role of education quality in economic growth. World Bank Policy Research Working Paper 4122.

Hattie, J. (2003). Teachers Make a Difference, What is the research evidence. Building Teacher Quality: What does the research tell us? Melbourne: ACER.

Jenset, I. S., Hammerness, K., & Klette, K. (2017). Grounding Teacher Education in Practice Around the World: An Examination of Teacher Education Coursework in Teacher Education Programs in Finland, Norway, and the United States. Oslo: Journal of Teacher Education.

O’Donoghue, T. (2018). Teacher education in Australia in uncertain times. Education Research and Perspectives, 45, 33-50.

OECD. (2019). TALIS 2018 Results (Volume I): Teachers and School Leaders as Lifelong Learners. Paris: OECD Publishing.

OECD. (2019). Teachers and School Leaders as Lifelong Learners. Paris: OECD Publishing.

Pilcher, S., & Torii, K. (2018). Crunching the number: Exploring the use and usefulness of the Australian Tertiary Admission Rank (ATAR). Melbourne: Mitchell Institute.

Plunkett, M., & Dyson, M. (2011). Becoming a teacher and staying one: examining the complex ecologies associated with educating and retaining new teachers in rural Australia? Australian Journal of Teacher Education, 36(1), pp. 32-47.

Social Research Centre. (2020). 2019 Student Experience Survey. Retrieved from https://www.qilt.edu.au/docs/default-source/ses/ses-2019/2019-ses-national-report.pdf?sfvrsn=6486ec3c_10

Teacher Education Ministerial Advisory Group. (2014). Action Now: Classroom Ready Teachers. Canberra: Teacher Education Ministerial Advisory Group.

Teacher Education Ministerial Advisory Group. (2014). Issues Paper. Canberra: Department of Education.

Teaching performance assessment: Program Standard 1.2 Fact Sheet. (2020, 01 10). Retrieved from AITSL: https://www.aitsl.edu.au/docs/default-source/initial-teacher-education-resources/tpa/tpa_program-standard-1-2_fact-sheet_for-website.pdf

Varadharajan, M., Carter, D., Buchanan, J., & Schuck, S. (2020). Career change student teachers: lessons learnt from their in-school experiences. The Australian Educational Researcher. Retrieved from http://unsworks.unsw.edu.au/fapi/datastream/unsworks:64867/binfb76ba32-af40-4170-b10f-d254cd2034a2?view=true&xy=01

Yeigh, T., & Lynch, D. (2017). Reforming initial teacher education: a call for innovation. Australian Journal of Teacher Education, 42(12), pp. 112-127.