The key messages in this Spotlight reveal that:

- To ensure strong student outcomes, we need a sustainable supply of high-quality teachers with the right set of skills working in classrooms where they’re needed most.

- Teacher supply and demand is a complex equation with many interacting variables and inputs, and no easy answers. The evidence base for understanding teacher supply and demand is currently incomplete – some elements are known and quantifiable,

while others are more difficult to isolate given current data limitations.

- Emerging evidence suggests the pace of teacher workforce growth will not be able to keep up with increasing student demand. This is especially true in some geographical locations and subject areas.

- It is increasingly unlikely that the teacher supply pipeline will be sufficient to replace attrition due to retirement, let alone any additional, pre-retirement attrition. This is particularly concerning given the high proportion of teachers indicating

they intend to leave the profession due to pressures like excessive workloads and stagnating salaries.

- Initial teacher education (ITE) commencements decreased by 19% from 2017 to 2018, with a further 1% drop from 2018-2019.

- In addition to the supply pipeline through ITE, there are other factors affecting teacher supply and demand at the national and local levels that are more difficult to quantify including workforce attrition, demand for subject specialisations

and the casualisation of the workforce. The potential impacts of alternative channels of teacher supply such as migration, attracting mid-career changers into teaching and fast-tracking pre-service teachers into classrooms are largely unknown.

- In addressing current and future teacher shortages, strategies must aim to both attract and retain high quality teachers with the right skills, where they’re needed most. To do this, both supply through ITE and factors negatively impacting

the overall workforce experience need to be addressed.

Australian schools are facing a critical shortage of teachers that is likely to worsen in the coming years (Department of Education, 2022b). A growing student population combined with declining commencements into initial teacher education (ITE), a lack

of casual/relief teachers (CRTs), stressors impacting teachers’ decisions to stay in the profession, and the looming retirement of ‘baby boomer’ teachers have created a perfect storm of workforce challenges for Australia’s

education sector. This issue is dominating the national education discourse. Teacher shortages are also a global concern. Europe is facing similar challenges to Australia, with 35 of 43 education systems across the continent reporting teacher shortages

(European Commission et al., 2021). Globally, the UNESCO Institute for Statistics projects that 69 million additional teachers are needed to achieve universal primary and secondary education by 2030 (UNESCO, 2016).

On 12 August 2022, Australia’s Education Ministers met with teachers, school leaders, and other education experts to discuss issues and ideas to prioritise actions to address the issue of teacher demand, supply, and retention. Listening to the voices

of teachers and leaders, our Ministers committed to develop a National Teacher Workforce Action Plan by December 2022 and to take a national approach to increasing the number of people entering and remaining in the profession.

The Australian Government has begun processes working to fast-track migrant teachers, and states and territories are rolling out various policy changes seeking to boost the number of students entering teaching programs, as well as increase the supply

of quality teachers in classrooms across all states and territories, and in metropolitan, regional and remote areas. Many of these responses are not new, but projections of teacher shortages have given them increased urgency. Some strategies include:

- accelerated pathways into teaching

- scholarships for priority cohorts of teaching students

- enhancing supports available for early career teachers

- providing financial incentives and other supports for teachers to relocate and remain in the geographical locations and subject specialisations where they are needed most

- providing government owned and/ or subsidised housing in regional, rural and remote areas

- supporting teachers to retrain in specialist subjects experiencing shortages

- seeking to attract more international teachers

- communications and marketing campaigns to promote the teaching profession (Department of Education, 2022a).

Jurisdictions are heavily invested in attracting and retaining teachers. Western Australia (WA) is implementing pay rises to mitigate cost of living pressures and has committed $30 million to reduce compliance time and additional duties for teachers,

recognise weekend work, and put in place wellbeing measures. Victoria is focusing on workload issues and has promised 1.5 fewer face-to-face teaching hours for each teacher next year at a cost of $700 million for the 1,900 additional teachers that

will be required to achieve the aim (ABC News, 2022). Strategies for internship type programs are under consideration. For example, the Victorian and New South Wales (NSW) state governments are aiming to work with universities to get university students

into classrooms as early as six months into their ITE program to work as assistant teachers (Bita, 2022).

However, as the breadth and scale of policy responses demonstrate, issues of workforce supply are inherently complex. Teacher supply is influenced by a complicated interplay of factors, some of which are known and quantifiable through existing, nationally

available data and others that are more difficult to discern and measure. Using existing data, it is possible to predict national growth in school student enrolments to understand how teacher demand, at the aggregated national level, might change

in the coming years. However, supply and demand issues can be quite localised – what works in one location may not work in another. We have limited understanding of differences in demand across different local markets.

The Australian

Teacher Workforce Data (ATWD) initiative is a national project supported by all federal, state and territory governments, that provides detailed longitudinal data on the number and characteristics of pre-service teachers progressing through the ITE

pipeline, the characteristics of the teacher workforce and attrition, and will provide complex predictive analysis of supply by geographical location beginning from late 2022. From the ATWD and other sources, we have increasing data on the stressors

in the workforce that might lead to deficits in the teacher supply pool. However, we have limited data on the factors that impact teachers who leave the profession, the availability of teachers with specific subject specialisations relative to workforce

demand, geographical differences in supply challenges, and the complex interplay of supply and demand across early childhood, primary and secondary teachers. Moreover, the ATWD is not funded to include demand data, limiting its capability to provide

a truly effective, cross-jurisdictional, labour market model.

There is evidence to suggest that teachers are leaving the profession due to some combination of excessive workloads, work environment, work stress and stagnating salaries. What is clear is that Australia’s current and impending teacher workforce

crisis will require nuanced strategies designed to address both the acquisition of new teachers and the retention of those currently in the workforce, based on comprehensive data. This Spotlight seeks to highlight what we know about teacher supply

to understand the challenges in building a sustainable and effective teaching workforce.

The demand for teachers grows as more students enrol in schools each year. From calculations using Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) population projections, we know that national student population growth will continue in the coming decade. However,

national trends are of limited value when trying to understand teacher demand in different geographical regions across the country. Though demand can be quantified at the national level, we simply do not have data that provides a more granular level

of projection. This is largely attributable to the highly localised nature of education in Australia whereby regional differences in schooling contexts are not captured across data sets. Moreover, the siloed nature of data from different sources makes

it difficult to model student enrolment projections across the different labour markets in Australia. This makes it challenging to pinpoint where growth in student enrolments will occur in the coming years, limiting our understanding of which kinds

of teachers are needed, and where. Given that policies targeting teacher supply and demand may work in some contexts but not others, these data limitations are crucial to our understanding of effective responses.

In 2021, there were 4,075,337[1] students enrolled in 9,581 schools across Australia. Between 2011 and 2021 an additional 567,579 students entered Australia’s education system, in line with population

growth. However, due to the unprecedented impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic, student enrolments only increased by less than one percent from 2020-2021 (0.7%). Changes in migration account for the difference in the standard growth rate, with net migration

of children aged 5-17 in 2020-21 being 29,360 lower than 2018-19 (ABS, 2021). While the pandemic has slowed the growth in student enrolments, on average, the Australian student population has been growing 1.5% per annum since 2008.

Calculations with ABS population projections[2] suggest it is likely student enrolments will continue to grow at a slightly lower average of 1.3% per annum between 2021 and 2031. This means that in the next

ten years the total Australian student population will grow by half a million, a 13% increase in comparison to 2021. This growth will be similar at the primary (1.3% per year) and secondary (1.2% per year) levels.

What this national trend analysis does not reveal, however, is the types of teachers that will be required to meet this growing student demand, nor where they are needed most. There is a continued lack of ‘demand’ data, which systems and sectors

need for accurate workforce modelling. Enrolments in different school types show distinct patterns. Primary enrolments decreased by 0.6% from 2020 (1,894,535) to 2021 (1,882,803). Secondary enrolments increased by 0.7% in the same period (from 1,218,854

in 2020 to 1,227,817 in 2021). Combined school enrolments grew 3.6% from 2020 (882,204) to 2021 (913,763), while special school enrolments grew 1.2% in the same period (from 50,365 to 50, 954).

Important jurisdictional and contextual differences across Australia require a more nuanced examination of teacher demand. Some information is available to provide this nuance, while much is not. We know there are differences in trends in population growth

between capital cities and other areas, at a national level. According to the ACARA School Profile, since 2008, the student population has grown faster in major cities and regional areas compared to outer regional, remote and very remote areas. Total

enrolments in remote and very remote areas have been declining, particularly in the last five years (on average, by 0.5% per year in remote areas and 0.7% per year in very remote areas).[3] However, while

enrolments in remote and very remote areas may be declining, anecdotal evidence suggests we currently cannot provide or retain the number of teachers needed in these areas.

Like student enrolments, at the national level the teaching workforce has been growing year on year. In 2021 there were 336,408 teachers in Australian schools, a 2.3% increase from 2020 (328,812).[4] On average,

the total teaching workforce has grown 2.3% per year since 2017. Forty-one percent of these teachers work in primary school settings, 31% in secondary, 25% in combined and 3% in special schools – this workforce split between school types has

been relatively stable since at least 2008. Since 2017, the primary teaching workforce has grown an average of 2% per year while the secondary workforce has grown an average of 2.2% per year.[5] Like enrolments,

the teaching workforce has been growing faster in major cities (2.5% per year since 2017) and inner regional areas (2.1%) than outer regional (1.3%), remote (0.5%) or very remote (0.7%) areas. While these data do not reveal a teacher shortage, teacher

supply is more nuanced than national figures suggest.

The data used to derive these historic trends in the teacher workforce, the ACARA School Profile, captures data for each school in Australia whereby schools report ‘the number (and full time-equivalent) of full-time and part-time teaching staff

members.’ This head count is unlikely to capture CRTs or registered early childhood teachers not working in schools and does not include registered teachers not working in schools. While a headcount of teaching staff at schools is important,

the total workforce must exceed this number so that there are casual staff available to backfill teachers when required. We know from the Australian Teacher Workforce Data (ATWD) initiative that roughly 10 percentof all teachers are CRTs.[6] At present, we havelimited national data on the casual teaching workforce.[7] The lack of longitudinal data on this population is problematic for assessing workforce trends

and modelling future supply issues. Unlike the ACARA School Profile, the ATWD has visibility of what is often termed the latent workforce, or the teachers currently working outside of teaching and school leadership, with teaching qualifications. Within

the latent workforce there may be registered teachers who intend to return to teaching or are available to fill workforce gaps. However, the size of this cohort and their motivations for maintaining registration while not teaching are unknown and

as such, it is unclear to what extent this group of registered teachers can contribute to alleviating teacher shortages.

Sectors and jurisdictions have responded to the urgent need for workforce related data and conducted their own modelling to estimate the number of new teachers required in coming years. In their submission to the Quality Initial Teacher Education (QITE)

Review in 2021, Catholic Schools NSW estimated a 15% workforce shortfall by 2030, driven largely by a reduction in the number of graduate teachers and attrition resulting from the retirement of ‘baby-boomer’ teachers (Catholic Schools

NSW, 2021). Similarly, the NSW Teachers Federation estimates that based on growth in the student population, NSW government schools will require between 11,100 and 13,700 additional teachers by 2031, a 20-25% increase on 2020 staffing levels (Rorris,

n.d.).

Existing modelling for future teacher supplyassumes the current relative stability of student-teacher ratios will continue (any reduction in this ratio would require additional teachers).[8] Additionally,

changes in teacher workload may also affect supply modelling. At present, evidence indicates teachers are working around 1.3-1.5 times as many hours as they are paid to work (AITSL, 2022). This excessive workload is negatively impacting teacher retention

(discussed further below - What do we know about teacher attrition?). If work conditions need to be altered to reduce teacher workloads, which may boost teacher retention by preventing burnout, this may generate a larger shortfall

in teacher supply.

The Australian Teacher Workforce Data (ATWD)

The ATWD initiative is building the evidence base that will inform the future of the teaching profession. By connecting initial teacher education data, graduate outcomes data, regulatory authority data, and teacher workforce experiences data from

across Australia, the ATWD is providing nationally consistent data on variables like how many teachers we have, how many graduates get jobs, the types of contracts teachers are employed under, teacher career paths and experiences, and how many

teachers are entering and leaving the profession. The ATWD is a joint initiative between, and is funded by, all state, territory and Commonwealth governments. It is being implemented by AITSL in partnership with the Australian Government Department

of Education, the states and territories, teacher regulatory authorities and the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW).

To find out more about the ATWD and its benefits to education in Australia visit:

https://www.aitsl.edu.au/research/australian-teacher-workforce-data

https://www.aitsl.edu.au/research/australian-teacher-workforce-data/key-metrics-dashboard

Overall, data relating to the ITE pipeline conveys a troubling trend. Fewer people are studying ITE, and this is particularly true in the larger states like NSW and Victoria. Given that all states and territories have witnessed declines in ITE completions

in recent years, workforce strategies that rely on attracting interstate graduates into teaching roles are unlikely to work when the overall pool of graduate teachers is shrinking. While the downward trend is evident for all program types, a sharp

recent decline in the number of ITE students commencing a primary program is particularly concerning given population projections of increased growth in primary enrolments in the next ten years. With fewer people entering ITE programs in recent years,

falling completion rates are likely to worsen as fewer pre-service teachers move through the ITE pipeline. While there are alternate pathways into teaching, like skilled migration, the actual number of teachers supplied to the workforce via alternative

routes is unknown.

The ITE pipeline

New teachers enter the workforce either through the completion of an accredited Australian ITE program, an approved skilled migration pathway or in some cases by gaining alternative authorisation to teach through a state/territory regulatory authority.

ITE data is published through the ATWD, which is updated annually as new data becomes available.

Commencements

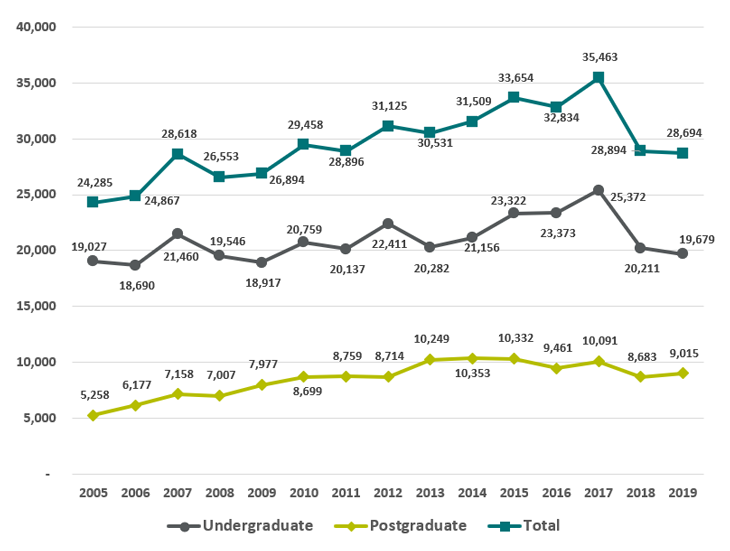

The most current ITE commencements data reveals a troubling downward trend in recent years, after a decade of solid growth. As shown in Figure 1, after a peak in 2017 of 35,463, commencements decreased considerably in 2018 by 19% (28,894) and dropped

a further 1% in 2019 (28,694). By all indications from jurisdictions, this decline has likely continued.[9]

While this downward trend is evident for both undergraduate and postgraduate commencements, there has been a larger decline for undergraduates. Compared to the peak of 2017 (25,372) undergraduate commencements dropped 22% by 2019 (19,679), while postgraduate

commencements dropped 11% in the same period (from 10,091 to 9,015).

Figure 1. ITE commencements, by level and year

While most students commence their program of study on campus (internal study mode), proportionally, internal commencements have been gradually decreasing while external study (off campus, online study) has been increasing. Between 2005 and 2019 internal

commencements dropped 20 percentage points and external commencements increased 13 percentage points in the same period. This national trend has occurred in most jurisdictions (with the exceptions of ACT and NT). While total commencements decreased

between 2017 and 2018, external commencements increased by 6% from 2018-2019. Study mode is an important factor when examining teacher supply. The data supplied here by the ATWD reflects the home state residence of the students. Most students intend

to work in their home state (AITSL, 2020). With the rise of online ITE, students are increasingly able to study in one location and reside in another. This has important ramifications for modelling teacher supply because the pipeline in any jurisdiction

“is not simply the number of students graduating from education providers in that state or territory. Instead, it is the number of ITE students who reside in that state or territory, regardless of where they studied. The difference is, in some

cases, substantial” (AITSL, 2020, p. 17).

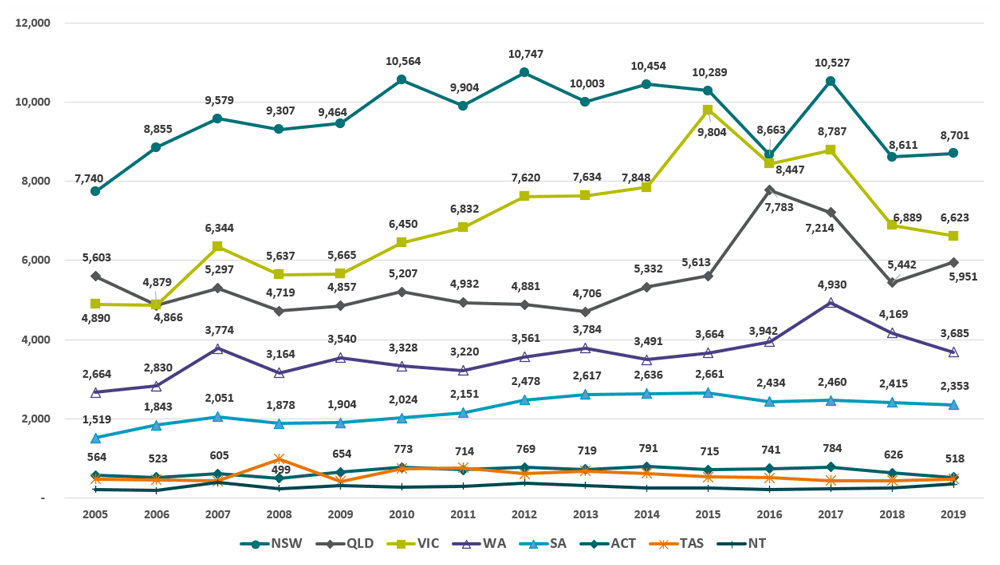

While longitudinal trends have differed across states and territories, these declines in commencements from 2017-2019 occurred in most jurisdictions. The two largest states, NSW and Victoria, constitute more than half of all commencements. Both states

saw declines from 2017 to 2018 (18% drop for NSW from 10,527 to 8,611; and 22% drop for Victoria from 8,787 to 6,889). Victorian commencements declined a further 4% from 2018 to 2019 (6,623), while NSW commencements increased 1% (to 8,701 in 2019)

in the same period. Overall, despite a peak in 2017, commencements in NSW appear to be trending downwards to levels not seen since the mid-2000s. Similarly, in Victoria it appears commencements are declining from a peak in 2015 to levels consistent

with 2010-2011.

In Queensland, commencements peaked in 2016 at 7,783 then dipped 7% to 7,214 in 2017. Queensland saw a sharp 25% drop in 2018 (5,442), followed by a 9% increase in 2019 (5,951). Commencements in WA appear to be following a similar trend. After a peak

in 2017 (4,930), commencements declined by 15% in 2018 (4, 169) and a further 12% in 2019 (3,685).

Like NSW, commencements in the Australian Capital Territory (ACT) peaked in 2017 (784), however since then, ACT has experienced the largest relative decline of any jurisdiction. Commencements dropped 20% in 2018 (626) and a further 17% in 2019 (518).

This represents a total decline in commencements of 34% from 2017-2019 in the ACT, to levels not seen since the mid-2000s.

Figure 2. ITE commencements, by state and year

Further examination of commencements data reveals that the drop in 2018 and 2019 is largely attributable to fewer domestic undergraduate students commencing ITE programs. An examination of the basis of admission for undergraduate commencements reveals

that these declines do not appear to correlate to the policy change requiring a minimum ATAR for entry into an ITE program. The proportion of ITE commencements entering on the basis of an ATAR over 80 has not significantly changed over time, rather

the number of undergraduate students commencing on the basis of ATAR has declined. This suggests school leavers are entering ITE programs via non-ATAR related mechanisms. As such, it does not appear that strategies targeting high achieving school

leavers, by setting higher ATAR cut-offs, adversely affected ITE commencements.

However, there was a key policy change in 2017 that coincides with this decline. By 2012, a demand-driven system (DDS) for universities was fully implemented across Australia. This meant that unlike the previous quota system, there were no caps on the

number of students universities could enrol in Commonwealth Supported Places (CSP). The sharp rise in ITE commencements between 2005 and 2017 (33% increase) suggests universities took advantage of this new system and increased the number of CSP places

in their ITE programs in this period. However, in December 2017 there was a significant change in the tertiary funding model. As part of the Mid-Year Economic and Fiscal Outlook (“MYEFO”), the Australian Government announced a funding

freeze on CSPs. While this freeze did not place a specific cap on the number of places a university could offer to prospective students in any course, it essentially ended the DDS model because the total level of Commonwealth Grants Scheme (CGS) funding

associated with domestic undergraduate students that each university was eligible to receive for both 2018 and 2019 was capped at the 2017 funding level.

As shown in Figure 2 the drops in commencements after 2017 were most pronounced in the larger states and the ACT. Common across these states and territories is the presence of relatively large universities with campuses across the states and territories

most affected by declining commencements. These universities would have larger capacity to increase or decrease intake into courses such as ITE by relatively large numbers in response to changes in funding and resourcing opportunities. This would

seem to be reflected in an increasing intake from 2005-2017, in particular among the larger states and ACT, followed by sharp declines in 2018 and 2019. It would seem likely then, that changes away from demand funding to capped funding may have had

a significant impact on intake into ITE programs in large universities in larger states such as NSW, as well as the ACT. Available data certainly indicates that there has been a decline in the number of students commencing ITE in these jurisdictions.

Whether this is directly attributable to the change in funding model is not visible in currently available data (the number of students who commence an ITE program in a CSP is not available).

Completions

Several policies that Ministers are pursuing to mitigate the teacher shortage are aimed at increasing the number of students entering the ITE pipeline. For example, paid internships may attract mid-career changers into teaching, increasing the number

of ITE students, particularly postgraduate students. We know that postgraduate ITE students tend to complete their ITE program at a higher rate than undergraduates, and finish their shorter degrees in, on average, 2-4 years (compared with 4-8 for

undergraduates). If successful, such strategies to attract mid-career professionals who already hold an undergraduate degree into teaching programs could boost graduate teacher supply in as little as 2 years.

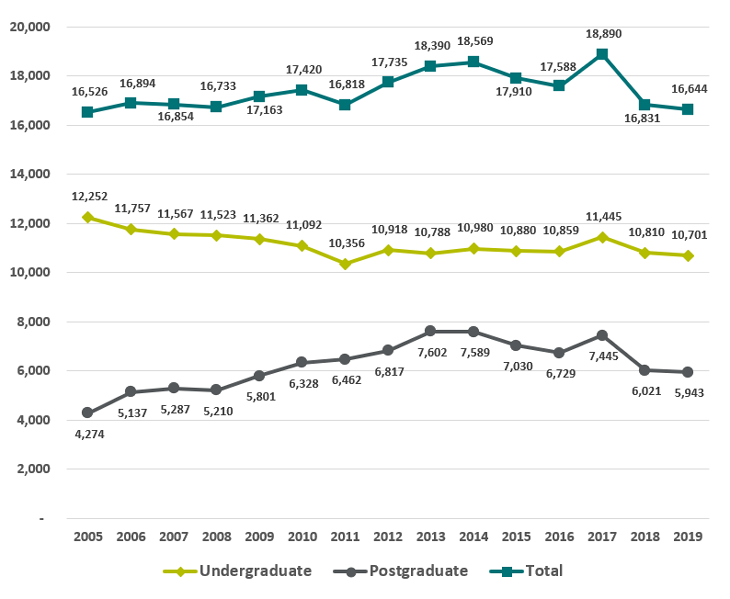

While ITE commencements have been declining, the number of students completing ITE programs has also dropped in recent years. After a peak of 18,890 completions in 2017, completions dropped 11% in 2018 (16,831) and a further 1% in 2019 (16,644), to levels

not seen since the mid-2000s. This drop in completions was considerably worse for postgraduates than undergraduates. Compared to the peak in 2017 (undergraduate: 11,445; postgraduate: 7,445), postgraduate completions dropped 20% by 2019 (to 5,943)

while undergraduate completions dropped 7% (10,701).

This trend is not due to lower commencements; completion rates have also declined since 2005. Six-year completion rates fell approximately 1 percentage point a year (from 61% to 52%) between those starting in 2005 and those starting in 2013. Six-year

completion rates for all undergraduate ITE programs declined for cohorts commencing between 2007 (early childhood: 54%, primary: 60%, secondary: 51%) and 2014 (early childhood: 48%; primary: 50%; secondary: 50%). During this period, undergraduate

ITE students in primary education programs largely had higher six-year completion rates, which ranged between 50% (2012) to 62% (2009), than those in early childhood, which ranged between 48% (2014) to 60% (2008), and secondary education programs,

which ranged between 48% (2011) to 54% (2008).

While the shift to two-year postgraduate ITE programs coincided with a drop in postgraduate completion rates around 2015, postgraduate completion rates are higher than undergraduate completion rates, though they have also declined over time. Two-year

completion rates for postgraduate ITE programs declined for cohorts commencing between 2005 (82%) and 2014 (67%) and dropped further for the period from 2015 through 2017 (55-58%). Four-year completion rates for postgraduate ITE programs also declined

for cohorts commencing between 2005 (81%) and 2014 (77%).

Figure 3. ITE completions, by level and year

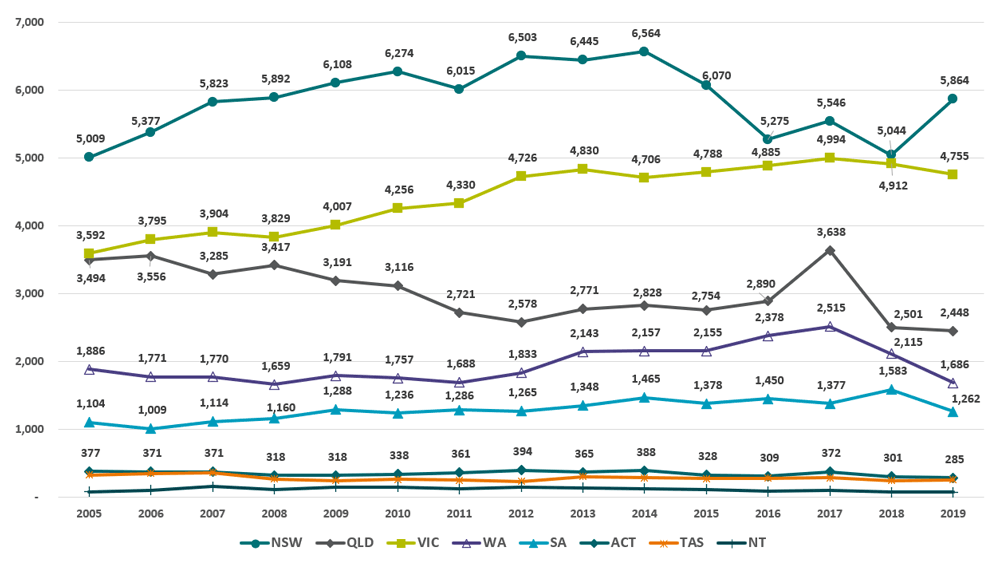

As per commencements, most students who complete an ITE program reside in either NSW or Victoria – in 2019, these states constituted 64% of all ITE completions, combined. This means almost two-thirds of Australia’s graduate teachers live in

these states. Concerningly, completions are trending downward in NSW and have flat lined in Victoria in recent years. Similarly, completions in Queensland, which constitute around 15% of ITE program completions, are declining. Overall, despite some

fluctuations, all states have seen declining completion rates in recent years. Given declining commencements, these drops in completions will likely worsen in the coming years as students move through their ITE programs in smaller numbers.

In NSW, completions peaked in 2014 (6,564) and declined by 8% in 2015 (6,070) and a further 13% in 2016 (5,275). Despite a 16% increase from 2018 (5,044) to 2019 (5,864), NSW completions are at levels consistent with 2006-2008. Victorian completions peaked

in 2017 (4,994) following several years of consistent 2% growth, then declined by 2% in 2018 (4,912) and a further 3% in 2019 (4,755). Completion numbers in Queensland have dropped lower than the first year of data collection (2005). After a peak

in 2017 (3,638), Queensland completions declined 31% in 2018 (2,501) and a further 2% in 2019 (2,448).

In WA, completions steadily increased each year between 2011 (1,688) and 2017 (2,515). However, this trend reversed sharply in 2018 (2,115) and again in 2019 (1,686), for an overall decrease of 33% between 2017 and 2019.

Unlike the other states and territories, completions in South Australia (SA) peaked in 2018 (1,583) but dropped 20% in 2019 (1,262). The smaller jurisdictions, ACT, Tasmania and the Northern Territory (NT), experienced drops in completions between 2017

and 2018. Though Tasmania bounced back slightly in 2019 (253, up 4% from 244 in 2018), ACT (285 in 2019) and the NT (73 in 2019) completion rates declined even further, to levels lower than the mid-2000s.

Figure 4. ITE completions, by state and year

Migration

Australia has a long history of teacher immigration. Skilled migration helps to broaden the pool of appropriately qualified and experienced teachers in Australia. It is also beneficial to Australia’s diverse student population - over 20 percent

of students in Australian schools speak a language other than English at home, but the teaching profession in Australia is predominantly comprised of monolingual English speakers (ACARA, 2021a; Mckenzie, Weldon, Rowley, Murphy, & Mcmillan, 2014).

Teachers with competencies in different languages and cultures are valuable to all Australian students (Bense, 2016). Migration of skilled workers is viewed as key to Australia’s economic recovery from COVID-19. Expansion of the skilled workforce,

including in regional and remote areas, has been flagged by a number of industries as being critical to economic recovery (Lim, Nguyen, Robinson, Tsiaplias, & Wang, 2021). However, currently it is not known how many of these suitable individuals

seeking to migrate to Australia actually do so, nor how many are successful in securing employment in teaching, nor how long they stay in teaching.

AITSL provides skills assessment services to teachers who wish to migrate to Australia. AITSL’s Assessment for Migration (AfM) function delivers skilled migration assessments on behalf of the Australian Government. AITSL has delivered this function

since 2006 (previously as Teaching Australia). The AfM process for assessing qualifications ensures that international teachers meet the standards required of Australian teachers to teach in a classroom.

The AfM process supports individuals who wish to migrate to Australia as a skilled migrant under one of eight

teacher occupations (AITSL, 2021a). AITSL undertakes a skills assessment at the level of the occupation nominated by the applicant and uses criteria that align with the national framework for teacher registration to assess each application. In 2021-2022,

AITSL delivered over 2,200 suitable skilled migration assessment outcomes to teachers seeking to migrate to Australia. This builds on the 1,188 suitable skilled migration outcomes assessed in the previous year. The longitudinal data in the ATWD will

enable future analysis of the success of this alternative pathway into teaching by monitoring how many end up teaching and where.

Assessment for Migration

The AfM skills assessment is a qualifications-based assessment. Applicants for all occupations are assessed against two criteria; qualifications and English language proficiency which must be met to achieve a suitable outcome. AITSL’s skills

assessment is intended for migration purposes and forms part of the broader visa application process. The criteria are comparable with current standards for accredited ITE programs delivered in Australia. They are also aligned with the nationally

consistent approach to teacher registration.

Alternative authorisation to teach

State and territory teacher regulatory authorities have their own policies for allowing people to teach in schools who do not meet qualification requirements for registration as a teacher. Applicants applying for alternative authorisation to teach may

possess specialist skills for teaching a certain subject, may be progressing through a Teach for Australia program, or may be in the final year of their ITE program. While these policies vary between jurisdictions, the impetus for allowing non-registered

people to teach is often to address workforce shortages and fill hard-to-staff positions (hence, the prospective employer or school initiates the process).

For example, in Victoria, the permission to teach (PTT) policy was updated in April 2022 to support the implementation of the Victorian tutor learning initiative announced in 2021 (Victorian Institute of Teaching, 2022). An additional category was included

in the updated policy (PTT (Teacher Tutor)) specifically granting individuals supporting students to catch up on learning lost due to the COVID-19 pandemic, permission to teach. In addition to a variety of general content and skill related eligibility

requirements, individuals applying for PTT (Teacher Tutor) need to have previously held teacher registration in Victoria. This demonstrates how jurisdictions may be using policies, like PTT, as levers to address critical shortages of teachers.

State-based data indicates that the number of PTTs are usually quite low – in Victoria there were 693 PTTs granted in 2019 and 401 granted in 2020 (Victorian Department of Education and Training, 2021b). It is possible that this number has increased

in 2021 and 2022 following the PTT policy change in response to the tutoring program. In Queensland, the number of PTTs increased from 2019 (178) to 2020 (211) (Queensland College of Teachers, 2021). These numbers have increased even further in 2021

(320) and 2022 (491) indicating schools are increasingly turning to alternative teaching pathways to source teaching staff (O’Flaherty, 2021; Rafferty, 2022).

The available data indicates that the number of individuals teaching under a PTT are low, though, as shown in Queensland, it is possible that there has been an increased demand for this teaching pathway in 2021 and 2022. Longitudinal data that can pinpoint

possible trends in geographic locations and subject areas where PTTs are deployed would be useful inputs to the teacher supply puzzle because PTTs offer some indication of where teacher shortages may be most pronounced.

Primary and secondary teachers

We know that teacher demand will increase over the next decade – student enrolments will grow by 1.3% per year at the primary and 1.2% at the secondary levels. We also know that ITE commencements and completions have declined in recent years, across

jurisdictions. Concerningly, these declines have been quite pronounced for primary ITE programs.

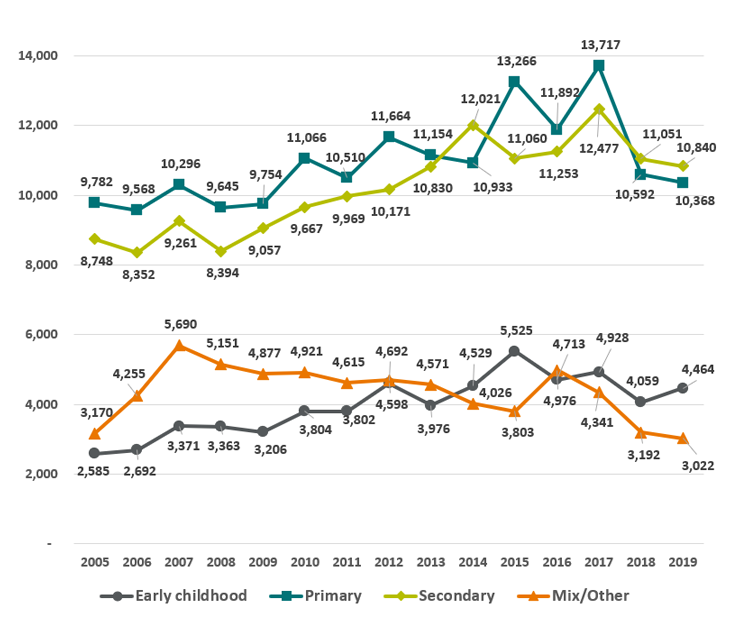

In 2019 most ITE students commenced either a primary (36%, n=10,368) or secondary (38%, n=10,840) program. Since 2005, there has been a 5-percentage point increase in the proportion of early childhood program commencements, from 11% to 16%.[10] All program types experienced drops in commencements between 2017 and 2018 – primary, secondary and mixed programs dropped even further from 2018 to 2019. In total, from 2017 to 2019, primary commencements decreased

24% (from 13,717 to 10,368) while secondary commencements dropped 13% (from 12,477 to 10,840). This sharp drop for primary commencements is likely to have negative consequences for primary teacher supply in the coming years as fewer pre-service teachers

move through a primary ITE pathway.

Figure 5. ITE commencements by program type and year

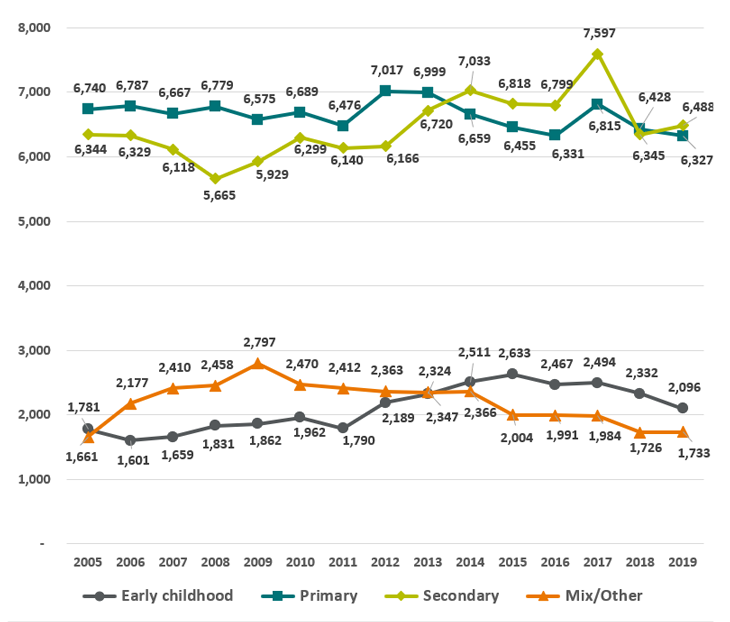

In 2019 most ITE students completed either a primary (38%, n=6,327) or secondary (39%, n=6,488) program. Since 2005, there has been a 2-percentage point increase in the proportion of early childhood program completions, from 11% to 13%. All program types

experienced drops in completions between 2017 and 2018 – primary and early childhood programs dropped even further from 2018 to 2019, while secondary completions increased by 2%. In total, in comparison to 2017, by 2019 early childhood completions

declined by 16% (from 2,494 to 2,096) primary completions decreased 7% (from 6,815 to 6,327) while secondary completions dropped 15% (from 7,597 to 6,488).

Figure 6. ITE completions by program type and year

Early childhood teachers

Early childhood teachers play a vital role in Australia’s education system, and they are an important cohort in the teacher workforce. Evidence consistently demonstrates the significant contribution early childhood teachers make to student learning

outcomes (Warren & Haisken-Denew, 2013).

As shown in Figure 6, the number of people completing an early childhood ITE program has declined in recent years to just over 2,000 in 2019. In 2021, there were 12,737 early childhood service providers delivering pre-school programs to 339,015 children

aged 4-5 (ABS, 2022a). At present, it is difficult to quantify how many early childhood teachers are working across the country. According to the ATWD, in 2018 approximately 6% of registered teachers were working in early childhood services (around

20,000 teachers).[11] The National Skills Commission (NSC) Labour Market Insights estimates there are approximately 50,400 degree-qualified early childhood teachers working either full-time or

part-time across Australia in pre-primary settings. The NSC projects strong growth in the number of early childhood teacher job opportunities over the next five years – 22% increase to 2026, an additional 10,600 jobs (National Skills Commission,

2021).

The provision of early childhood education and care services in Australia is regulated through the National Quality Framework (NQF) and monitored by the Australian Children’s Education & Care Quality Authority (ACECQA). There are situations

where early childhood service providers are unable to meet their requirements under the NQF and can apply for a service waiver to keep operating. Waivers can relate either to the physical environment of the service or staffing arrangements. These

waivers can indicate where the early childhood sector may be struggling to operate due to staff shortages. The number of services requiring staffing waivers to operate has increased in recent years. In 2013-2014 around 4-5% of all services across

Australia required staffing waivers. This increased to 7% in 2020 and 8.5% in early 2022 (ACECQA, 2022). Staffing waivers are more common in outer regional (14.2% of services) and remote areas (13.1%) and least common in major cities (7.8%). There

are also differences across the states and territories – staffing waivers are most commonly required in WA (14.3% of services) and Queensland (14%) and least common in the NT (5.3%) and Victoria (2.7%).

What is not clear from this data is the cause of the staffing waiver. That is, whether the staff shortages are due to a lack of registered early childhood teachers available to teach pre-school programs, or due to insufficient educators available for

the service to adhere to the educator to child ratios set out in the NQF (which vary by jurisdiction and service type). Regardless, the rise in waivers signals shortages in one or more components of the early childhood workforce.

Subject specialisations

Data about vacancies offer interesting insights into strains on teacher supply at a granular level. For example, in Victoria, the government school secondary subjects with the highest ‘no appointment rate’ [12] in 2020 were ‘digital technology’ (36%), ‘design technology’ (34%) and ‘languages’ (30%). ‘Mathematics’ (19%) and ‘science’ (20%) had higher no appointment rates than ‘English’

(17%) and ‘humanities-geography’ (12%). This data supports emerging evidence from the ATWD relating to ‘out-of-field’ teaching. For example, in 2018, between 34-46% of ‘design and technology’ teachers were teaching

out-of-field (AITSL, 2021)[13]. Overall, around 1 in 5 teachers are teaching out-of-field across all subjects (AITSL, 2021). This demonstrates the need for greater information about teachers’ subject

specialisations to better assess strains on teacher supply and ensure the right teachers are where they’re most needed.

Regional and remote teachers

Vacancy rates demonstrate there are geographic-specific strains on teacher supply. While we know anecdotally and from media reports that regional and remote areas are having trouble finding suitable teaching staff, data on teacher supply by geolocation

is largely unavailable at a consistent, national level. There is some state-based data to indicate there is a staffing problem in regional and remote areas. In Victorian government schools, application rates shrink

[14] with increasing remoteness – in major cities, the application rate for primary schools is 31.3 and secondary schools is 12.5; in outer regional and remote areas the application rates drop considerably

to 5.3 for primary and 3.7 for secondary. This means that in major cities, particularly at the primary level, there are many more teachers applying for vacant positions than in regional and remote areas. As such, there is a greater likelihood of schools

finding an appropriate candidate to fill vacancies in metropolitan schools compared to remote schools.

Casual/relief teachers

A consistent theme in recent media coverage of teacher supply has been the challenge principals are facing in finding CRTs. These teachers play an important role in the teaching workforce by ensuring continuity in students’ education when regular

classroom teachers are absent. Given the COVID-19 pandemic, this need for backfill options has become even more critical in recent years. In fact, evidence suggests teachers have been taking more time off due to illness – data from the Queensland

Department of Education show teachers in Queensland government schools took 35,000 more sick days in the 2020-21 financial year compared to the year prior (Bennett, 2021). This increase is largely attributable to health advice to isolate in the event

of illness to stop the spread of COVID-19 and protect others in the community. It is possible, given the increases in COVID-19 cases during winter 2022 as well as the influenza season, that this trend of increasing teacher absences has continued and

possibly worsened. While such absences increase the need for CRTs there are additional factors at play that may have diminished the potential pool of casuals, particularly in some areas. For example, some state governments implemented programs to

deliver small-group, intensive teaching or tutoring to mitigate potential gaps in learning caused by extended periods of online education during the COVID-19 pandemic.

It is possible that such strategies have impacted the latent workforce and availability of CRTs. It also appears CRTs are increasingly transitioning into temporary roles in NSW, which reduces the overall pool of CRTs available to support schools (NSW

Department of Education, 2021). We know that in the 2018 ATWD Teacher Survey a large proportion of CRTs reported being underemployed (just 7% worked full time hours) and working in casual roles because they were unable to secure ongoing or contract

roles (35%; AITSL, 2021). For early career teachers, this was an even greater problem with 57% reporting in 2018 that they were working as a CRT because they were unable to secure permanent employment (AITSL, 2021). It seems likely, therefore, that

the availability of contractual work (either for intensive learning support or temporary roles) would be attractive to those CRTs who would prefer ongoing employment rather than casual roles. Moreover, while 1 in 10 teachers are CRTs, this varies

by age group with teachers aged 60 or over twice as likely to be working in casual roles in 2018 (AITSL, 2021). Given this cohort of teachers are either at or approaching retirement age, it is possible older casual teachers are leaving the workforce,

thereby reducing the overall availability of CRTs.

At present, the casual teaching workforce in Australia is poorly understood and limited data are available. There is some data available in Victoria, from the Victorian ‘casual relief teacher census’ that was discontinued in 2019, that indicates

casuals are particularly needed in mathematics and science. In 2019, there were 159 ‘difficult to fill’ CRT vacancies in mathematics and 64 in science, compared to 5 in humanities-history and civics (Victorian Department of Education and

Training, 2021a). The rate of difficult to fill CRT vacancies at the primary level has also been increasing over time in Victoria from 339 in 2016 to 517 in 2019.

Casual/relief teachers

Casual/relief teachers will be a focus of future ATWD reports as the sample size of the cohort expands (Wave 2 onwards), and the collection of data on their contractual and teaching arrangements is better aligned with their experiences (Wave 4 onwards).

From Wave 4 onwards we will have access to greater understanding of the casual workforce including where, what sector and how many schools CRTs work at, the geographic area they cover and the hours they work.

A diverse workforce

A diverse workforce is a strong workforce. Evidence demonstrates that diversity, in terms of knowledge and expertise, age and abilities, cultural and linguistic backgrounds, gender and sexual identities, benefits everyone. Diversity makes teams smarter,

increases innovation, improves performance and is ethically important (AITSL, 2019). At present, there is clear scope to increase diversity in the teaching workforce.

Most teachers are women – in 2018 just 22% of the teaching workforce were men, though 31% of leaders were men. This gender disparity is even more pronounced in early childhood where just 1% of early childhood teachers were men in 2018 (AITSL, 2021b).

While a third of all secondary teachers are men, just 16% of primary teachers are men. Based on current ITE commencements and completions, this trend is unlikely to change – in 2019 73% (n=20,959) of commencing ITE students and 74% (n=12,280)

of completing ITE students were women, a trend that has been relatively stable over time in most jurisdictions.

While Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander learners constitute 6.2% of all students, just 2% of teachers are Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people (ABS, 2022b; AITSL, 2021b). In 2019 just 1% of commencing ITE students were Aboriginal and Torres

Strait Islander people, so this underrepresentation in the teaching workforce is unlikely to change.

A true understanding of teacher supply challenges must also consider the rate of attrition from the workforce and monitor the impact of policy responses targeting teacher retention. Emerging evidence indicates the current teacher supply pipeline may be

insufficient to cover workforce attrition due to retirement in the coming years. Furthermore, large numbers of teachers report intentions to leave the profession before retirement due to various workforce pressures. It is important to note that “intention

to leave” is not necessarily related to actual attrition. Understanding these workforce pressures is crucial to ensuring retention strategies have the best chance of success. The profession has repeatedly identified key issues affecting

the workforce experience, such as high workloads, stagnating salaries, red tape, educator wellbeing, leadership and school culture. These are some of the most critical levers when it comes to teacher retention. Helping schools, systems and sectors

understand how best to implement positive change in the workforce experience is a policy challenge that must be considered if we are to boost teacher retention and avoid increases in pre-retirement attrition.

At present, there is no national data and, therefore, insufficient evidence to ascertain longitudinal trends in teacher attrition in Australia. Reported teacher attrition varies by state and appears to be higher for early career teachers (Table 1). However,

attrition data is siloed, figures vary between jurisdictions and data is neither consistently captured [15] nor reported.[16] Reported attrition rates may

not capture cross-sectoral or cross-jurisdictional movement within teaching. As such, the only true measure of exits from the teaching workforce is retirement data, which is often combined with other sources of attrition for reporting (see Table 1).

The ATWD will do much to provide high quality attrition data over time, which will offer insight into teacher mobility and attrition at both the national and local levels, with visibility of cross-state and cross-sector movements. Currently, the ATWD

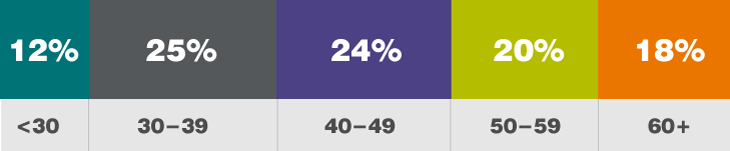

sheds some light on potential future trends relating to attrition from the teaching workforce. For example, in 2020, 18% of the teaching workforce were aged over 60 years (Figure 7) and, therefore, likely to retire within 5-10 years. In the 2018 ATWD

Teacher Survey, around 18% of respondents were in their first 5 years of teaching.[17] This would suggest that currently, the supply of new teachers balances out the exits of teachers reaching retirement

age. However, for this to remain true, these new, early career teachers need to be retained. Furthermore, the recent sudden drops in ITE commencements are yet to be seen in teacher workforce data. Given these drops in the ITE pipeline as well as the

pending retirement of baby-boomer teachers, it is highly possible that the incoming supply of teachers “will not be sufficient to replace retirement loss over the next five to ten years” (AITSL, 2021c, p. 25). The incompleteness of available

data, however, makes it difficult to determine by how much at this stage.

Figure 7. Age groups, registered teachers (all participating states/territories), 2020 (AITSL, 2022)

Any growth in retirement rates or increased attrition will have an important impact on overall attrition, leading to increased stress on teacher supply. This could be exacerbated if pre-retirement attrition also increases. It is, therefore, concerning

that several studies suggest an imminent loss of teachers across the profession.

The ATWD Teacher Survey found that in 2020, 21% of teachers reported intentions to leave the profession before retirement. A further 33% were unsure. Of those intending to leave before retirement, 9% intended to leave in one year or less (2% of total

workforce), and 51% (10% of total workforce) intended to leave within ten years (AITSL, 2022). The ATWD Teacher Survey sheds further light on issues relevant to the workforce experience and how this impacts teachers’ intentions to leave the

profession. Of the full-time teachers who responded to the survey in 2020, the median working hours reported as a percentage of contracted hours exceeded 1 FTE – in most jurisdictions (ACT, NSW, NT, SA) full time teachers reported working 145%

of their contracted hours in a typical week.

It is unsurprising then, that 86% of those respondents who indicated they intend to leave teaching cited reasons relating to workload and coping (work-related stress). The second most cited category of reasons to leave before retirement related to recognition

and reward (65%) – this includes both salary and the status of the profession in the wider community. Notably, those intending to leave due to the demands of professional regulation has declined since 2018 from 49% to 37% in 2020, which may

indicate that efforts to reduce red tape have been somewhat successful in reducing administrative burden and stress on teachers.

A recent study conducted by Monash University researchers (Heffernan, Bright, Kim, Longmuir, & Magyar, 2022) found similar results. When asked how long they intend to remain in the teaching profession, 41% (n=988) said they do not intend to leave,

while 7% (n=167) said 1 year, 19% (n=462) said 5 years, 12% (n=292) said 10 years and 21% (n=525) said ‘other’. The key reasons listed by those who indicated they do not intend to remain in the profession (59% of all respondents, n=1,446),

included “overwhelming workloads, negative impact of the job on respondents’ health and wellbeing and a sense of a lack of appreciation or poor treatment of teachers and the wider profession” (Heffernan et al., 2022, p. 200).

A sustainable workforce is one that is both future focused and prioritises wellbeing. Concerningly, a high proportion of teachers and school leaders report that teaching negatively impacts their wellbeing. In fact, in 2018 around three quarters of Australian

educators said their job negatively affects their mental health and more than half said they experience stress at work (Thomson & Hillman, 2020). Evidence also indicates that the COVID-19 pandemic has increased the already high levels of stress

on teachers (Heffernan, Magyar, Bright, & Longmuir, 2021).

It is important to note that reported intention to leave teaching will not necessarily result in actual attrition. International data suggests that rates of reported intention to leave the profession (when asked in a yes/no format[18])

of 30-40% may result in actual turnover closer to 10-15% (Räsänen, Pietarinen, Pyhältö, Soini, & Väisänen, 2020). Australian teacher attrition appears to be comparable to attrition in New Zealand. In 2020, 4.8% of

teachers in New Zealand left teaching (4.6% of primary and 5.1% of secondary teachers; New Zealand Ministry of Education, 2022).

Further investigation is required to understand how intentions to exit before retirement may translate to actual attrition. However, given that 10% of the total workforce indicated in 2020 that they intend to leave teaching within the next decade, and

with such high and consistent numbers of teachers indicating they intend to leave the profession well before retirement, teacher retention is a critical priority for reducing strain on teacher supply. It is crucial that measures designed to address

current and future shortages prioritise teacher retention.

Table 1: Comparison of available attrition data, by state.

Jurisdiction | Sector and role | Rate | Year | Definitions |

|---|

Victoria | Government early childhood teachers | 3.2% | 2020 | Early childhood attrition is defined as allowing early childhood registration to expire. In 2020, attrition from government positions was calculated by dividing staff headcount exits by the ongoing headcount staff on the government

workforce payroll.[19] In 2018, the attrition rate for the government workforce was calculated by dividing FTE staff attrition by the FTE of ongoing staff on the government workforce

payroll. Staff attrition numbers included those employed on an ongoing basis who left the teaching workforce during a calendar year.[20] |

5.6% | 2018 |

Government primary teachers | 4.1% | 2020 |

4.3% | 2018 |

Government secondary teachers | 5.3% | 2020 |

4.8% | 2018 |

Catholic primary teachers | 5.7% | 2020 |

4.7% | 2018 |

Catholic secondary teachers | 7.2% | 2020 |

5.3% | 2018 |

New South Wales | Government primary teachers | 3.9% | 2019 | Separations are defined as resignations, retirements (including medical retirements), terminations and deaths.[21] |

4.5% | 2018 |

4.9% | 2017 |

Government secondary teachers | 4.8% | 2019 |

5.2% | 2018 |

5.8% | 2017 |

Tasmania | Government teaching service staff aged less than 55 years | 1.2% | Year to March 2022 | Separation rate.[22] |

1.6% | Year to March 2021 |

Graduate teachers | 23.1% | Year to March 2022 | The separation rate for teaching service staff with 5 or less years’ service. This consisted of 54 (18.88%) resignations, 11 (3.85%) retirements, and 1 (0.35%) Other separation (‘Other’ denotes deceased employees,

transfers to different agencies, etc.). |

17% | Year to March 2021 | This consisted of 36 (15.3%) resignations and 4 (1.7%) retirements.[23] |

Australian Capital Territory | Government teachers | 4.5% | 2021 | Separation rate.[24] |

Western Australia | Government teachers | 5.4% | 2020 | Teacher retirements were calculated using the total number of retirements (541) and total school-based teaching staff (21,582) to give an approximate retirement rate of 2.5%. Total number of resignations (622) were used to calculate

an approximate resignation rate of 2.9%. These calculated rates were used to estimate an approximate attrition rate.[25] |

South Australia | Government teachers | 5.7% | 2021 | As of October 2021, government schools saw 815 separations from a total count of 14,282 teaching staff.[26] |

Queensland | Graduate teachers | 3.6% per year (14.3% overall) | 2009-2013 | The proportion of graduate teachers removed from the QCT Register within four years of being granted provisional registration between 2009 and 2013 was 14.27%.[27] |

Attracting new teachers and retaining existing teachers

The need to attract more people into the profession is urgent. However, a recent analysis of Australian print media coverage of education from 1996 to 2020 found a troubling trend – negative articles about teachers are the norm (Mockler, 2022).

Though positive, ‘good news’ stories are published, negative portrayals of teachers are vastly more common in the media, such as blaming teachers for declines in international test results. Recent media coverage of heavy workloads,

long working hours and staffing challenges are further examples of negative portrayals of the profession. While the challenges currently facing the workforce are important for the public to understand, it is also important to recognise that media

discourse has an impact on both attracting potential teachers into the profession and retaining existing teachers.

The data we have about teacher supply conveys a looming problem. ITE commencements and completions are dropping. This means the pipeline of new teachers ready to enter Australian classrooms in the coming years may not be able to keep up with natural attrition

in the workforce. It is even less likely the pipeline can compensate for any accelerated loss the workforce may have sustained during the pressures of the COVID-19 pandemic or any increased loss that may occur as teachers aged 60+ move into retirement.

Boosting the number of pre-service teachers in the ITE pipeline is vital to any teacher supply strategy. While shorter term solutions are needed to help schools cope with current shortages, it is also important to implement longer term strategies

that target retention and will ensure Australia’s supply of teachers is sustainable in future. This may involve a combination of funding-based polices that increase the number of CSPs available to universities for ITE programs, and recruitment

drives to increase the attractiveness of ITE courses for school leavers.

It is also crucial to understand where teachers are needed most and pursue policies most likely to get the right teachers into the right classrooms then retain them in the profession. Vacancy data supports what we are already hearing from the education

profession - there is a problem with unmet demand for teachers in certain subjects and geographic areas. The magnitude of this problem cannot be quantified with the limited data currently available. It is likely this issue varies across systems/sectors

and worsens with increasing remoteness and relative socio-economic disadvantage. In future, the ATWD initiative will fill many of these data gaps. With increasing access to national, linked data our ability to conduct more sophisticated labour market

modelling will improve our understanding of the national supply and demand trends in the teaching profession (AITSL, 2021d).This will enable jurisdictions to implement targeted policies aimed at building a sustainable teaching workforce.

Using a series of ABS datasets, population projections can be calculated for the Australian school student population in the next ten years (from 2021-2031; 2021 was chosen as the reference point for projecting a decade ahead because the ACARA School

Profile for 2022 was not yet available at the time of writing). This calculation involved a series of steps and assumptions. The following datasets were used:

- ABS population projections, Australia 2017-2066.

- Fertility assumption: medium fertility, mortality assumption: high life expectancy, net overseas migration (NOM): medium. Note: while the COVID-19 pandemic has undoubtedly impacted NOM, it is unclear what the longer-term ramifications will

be and, therefore, medium NOM was selected as a mid-range choice to be moderately conservative in population estimates.

- Ages: 3-19, years: 2017-2031

- This provides the estimated resident population (ERP)

- ABS schools, Australia.

- Table 66a Capped school participation rates for students aged 6-19 years, 2011-2021

- Table 42b Number of full-time and part-time students, 2006-2021

- ACARA School Profile, 2008-2021

School participation rates (SPR) were applied to the population projections to derive projected student populations to 2031. To do this, the SPR was manually calculated for students under 6, using table 42b which provides the number of students in each

year of schooling, by age. This calculation involved dividing the number of students at each age (in this case, ‘4 and under’ (4 year olds and 3 year olds combined) and ‘5’) by the total ERP given by the population projections

(the same methodology used to develop table 66a, which provides the SPR for the remaining school ages, 6-19). An average of the SPR was then taken for each age, to be applied to population projections for the years 2022-2031. To derive the school

student population, by year and age, the SPR (actual for 2017-2021, average of 2011-2021 for 6-19 year olds, average of 2017-2021 for <6) was applied to the population projections. This provided the size of the student population, by age and year

up to 2031.

The actual data from 2017-2021 was compared to these calculated projections using the longitudinal ACARA School Profile data from 2017-2021. This comparison showed that the calculated projections were within, on average, 0.6% of the observed student enrolment

numbers for the year 2017-2021, which suggests that for the purposes of examining overall trends in student populations in the next ten years, this method is sound and reliable.

Footnotes

- Australian student numbers and school numbers are derived from the ACARA School Profile, 2008-2021, an annually published list of all Australian schools.

- See appendix: Data sources and projections methodology

- Detailed data on school participation rates by age, (data published by the ABS which is required to calculate student population projections) is not published by geolocation, limiting student projections to the state or national level.

- ACARA School Profile, 2008-2021

- It is not possible to tell from this data what proportion of teachers in combined schools are primary teachers versus secondary teachers.

- The casual workforce is discussed further in the section titled What do we know about gaps in teacher supply?

- The ATWD initiative will provide a more accurate and detailed view of CRTs once all jurisdictions participate, and subsequent years of data are incorporated.

- This ratio varies slightly by sector, school stage and jurisdiction – nationally in 2021, the FTE student-teacher ratio was 14.5 at the primary level and 11.9 at the secondary level. (ACARA,2021b)

- At present, the 2019 data is the most recent data that has been supplied to the ATWD by the Department of Education - 2020 and 2021 data will be provided concurrently and likely be available in 2023.

- The examination of the source data suggests that while there has been an increase in 2019 relative to 2018 for early childhood commencements, there may be issues with data quality which means that this increase may in fact have been more evenly spread

between 2018 and 2019.

- As additional waves of data are added to the ATWD the true size of this population will become clearer. Note, some jurisdictions do not require early childhood teachers to hold teacher registration.

- Positions with no appointments by all vacancies tagged with a specific subject in the online system.

- Teaching a subject, they have not been directly trained to teach (through higher education study).

- Number of applications received per vacancy.

- Different terminology is used. In some cases, exit rates are reported (exit from the workforce) and in others, separation rates are used (separation from employer). Attrition rates are also reported in some jurisdictions, which may incorporate various

sources of turnover including, but not limited to, retirement, resignation (which can be either separation or exit, but is not always specified), termination and death.

- The ATWD initiative will provide a more accurate and detailed view of attrition once all jurisdictions participate, and subsequent years of data are incorporated.

- As not all new teachers are young, it is important to compare numbers for those approach retirement to early career numbers not the number of young teachers. Updated data on early career teachers will be available in future ATWD KMD releases.

- This is not the format used in the ATWD, and so numbers between these sources are not directly comparable.

- Victorian Department of Education and Training, 2021. Victorian Teacher Supply and Demand Report 2020, https://www.education.vic.gov.au/Documents/school/teachers/profdev/careers/teacher-supply-and-demand-report-2020.pdf

- Victorian Government Department of Education and Training, 2020. Victorian Teacher Supply and Demand Report 2018: Supplementary data report, https://www.education.vic.gov.au/Documents/school/teachers/profdev/careers/TSDR_2018-_Supplementary_Data_Report.pdf

- NSW Department of Education, 2021. Separation rates for permanent NSW government school teachers (2007-2019), https://data.cese.nsw.gov.au/data/dataset/separation-rates-for-permanent-nsw-public-school-teachers

- Tasmanian Government Department of Education, 2022. Key Data March 2022, https://publicdocumentcentre.education.tas.gov.au/library/Shared%20Documents/Key-Data-2022.pdf

- Tasmanian Government Department of Education, 2022. Key Data March 2022, https://publicdocumentcentre.education.tas.gov.au/library/Shared%20Documents/Key-Data-2022.pdf

- ACT Government Education Directorate 2021, Annual Report 2020-2021, https://www.education.act.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0008/1908665/EDU-2020-21-Annual-Report-downloadable-version.pdf

- Government of Western Australia Department of Education 2021. Annual Report 2020-21, https://www.education.wa.edu.au/dl/rn831kz

- South Australia Government Data Directory (Data SA) 2021. ‘Workforce Data by Separations and Unpaid Leave’ [data set], South Australian Government Data Directory, accessed 30 June 2022 https://data.sa.gov.au/workforce-data-separations-and-unpaid-leave.csv

- Queensland College of Teachers 2019. Attrition of Queensland Graduate Teachers 2019 Report, https://cdn.qct.edu.au/pdf/QCT_Qld_Graduate_Attrition_Report_2019.pdf

ABC News. (2022). Education Minister Jason Clare updated

after Teacher Workforce Roundtable. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=THCdN_Py_Iw

ABS. (2021). Overseas Migration. Retrieved September 15, 2022, from https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/people/population/overseas-migration/2020-21#age-and-sex

ABS. (2022a). Preschool Education, Australia. Retrieved September 16, 2022, from https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/people/education/preschool-education-australia/latest-release

ABS. (2022b). Schools, 2021. Retrieved August 22, 2022, from https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/people/education/schools/2021

ACARA. (2021a). School Profile 2008-2021 [Data Set]. Retrieved September 15, 2022, from https://acara.edu.au/docs/default-source/default-document-library/school-profile-2008-2021fa4e2f404c94637ead88ff00003e0139.xlsx?sfvrsn=49da4c07_0

ACARA. (2021b). Student-teacher ratios. Retrieved August 5, 2022, from https://www.acara.edu.au/reporting/national-report-on-schooling-in-australia/national-report-on-schooling-in-australia-data-portal/student-teacher-ratios

ACECQA. (2022). Waivers. Retrieved August 4, 2022, from NQF Snapshot website: https://snapshots.acecqa.gov.au/Snapshot/waivers.html

AITSL. (2019). Diversity in School Leadership. Retrieved August 5, 2022, from https://www.aitsl.edu.au/docs/default-source/research-evidence/spotlight/diversity-in-school-leadership.pdf?sfvrsn=93effa3c_10

AITSL. (2020). National

Initial Teacher Education Pipeline: Australian Teacher Workforce Data Report 1. Education Services Australia.

AITSL. (2021a). Assessment for Migration: Guide to applying for a skills assessment. Retrieved August 22, 2022, from https://www.aitsl.edu.au/docs/default-source/assessment-for-migration-forms/afm-forms-2021/afm_-application-guide_sept-2021.pdf?sfvrsn=5332da3c_2

AITSL. (2021b). Australian

Teacher Workforce Data, National Teacher Workforce Characteristics Report:

South Australia. Retrieved from https://www.aitsl.edu.au/docs/default-source/atwd/atwd2022/state-profile--south-australia.pdf?sfvrsn=e927a03c_2

AITSL. (2021c). Australian

Teacher Workforce Data National Teacher Workforce Characteristics Report. Education Services Australia.

AITSL. (2021d). Teaching Futures. Retrieved from https://www.aitsl.edu.au/docs/default-source/research-evidence/ait1793_teaching-futures_fa(web-interactive).pdf?sfvrsn=d6f5d93c_4

AITSL. (2022). ATWD Key Metrics Dashboard. Retrieved September 15, 2022, from Australian Teacher Workforce Data website: https://www.aitsl.edu.au/research/australian-teacher-workforce-data/key-metrics-dashboard

Bennett, S. (2021, October 6). Health advice behind Qld teachers’ 500k sick days in a year. The

Courier-Mail.

Bense, K. (2016). International teacher mobility and migration: A review and synthesis of the current empirical research and literature. Educational Research Review, 17, 37–49.

Bita, N. (2022, July 21). University students to ease teacher shortage. The Australian. Retrieved from https://www.theaustralian.com.au/nation/university-students-to-ease-teacher-shortage/news-story/8ce974b2ad55b104ffe56bdec18671dc?btr=641e3a195cda420a5778c4884cbca1af

Catholic Schools NSW. (2021).

Quality Initial Teacher Education Review: Submission. Retrieved from https://www.dese.gov.au/quality-initial-teacher-education-review/consultations/quality-initial-teacher-education-review-submissions/submission/12799

Department of Education. (2022a). Education Ministers Meeting Communique - 12 August 2022. Retrieved August 19, 2022, from https://www.dese.gov.au/education-ministers-meeting/resources/education-ministers-meeting-communique-12-august-2022

Department of Education. (2022b). Issues Paper: Teacher Workforce Shortages. Retrieved August 19, 2022, from https://ministers.education.gov.au/sites/default/files/documents/Teacher Workforce Shortages - Issues paper .pdf

European Commission, European Audiovisual and Culture Executive Agency, Motiejūnaitė-Schulmeister, A., De Coster, I., & Davydovskaia, O. (2021). Teachers in Europe: Careers, Development and Well-being (P. Birch, Ed.). Luxembourg: Publications

Office of the European Union.

Heffernan, A., Bright, D., Kim, M., Longmuir, F., & Magyar, B. (2022). ‘I cannot sustain the workload and the emotional toll’: Reasons behind Australian teachers’ intentions to leave the profession. Australian Journal of Education.

https://doi.org/10.1177/00049441221086654

Heffernan, A., Magyar, B., Bright, D., & Longmuir, F. (2021, April 7). How COVID has changed the way Australians think about teachers’ expertise and schooling. Retrieved August 17, 2022, from Monash Education website: https://www.monash.edu/education/teachspace/articles/how-covid-has-changed-the-way-australians-think-about-teachers-expertise-and-schooling

Lim, G., Nguyen, V., Robinson, T., Tsiaplias, S., & Wang, J. (2021). The Australian economy in 2020–21: The COVID‐19 pandemic and prospects for economic recovery. Australian

Economic Review, 54(1), 5–18.

Mckenzie, P., Weldon, P., Rowley, G., Murphy, M., & Mcmillan, J. (2014). Staff in Australia’s

Schools 2013: Main Report on the Survey. Retrieved from https://research.acer.edu.au/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1021&context=tll_misc

Mockler, N. (2022). No wonder no one wants to be a teacher: world-first study looks at 65,000 news articles about Australian teachers. Retrieved July 26, 2022, from The Conversation website: https://theconversation.com/no-wonder-no-one-wants-to-be-a-teacher-world-first-study-looks-at-65-000-news-articles-about-australian-teachers-186210

National Skills Commission. (2021). Early Childhood (Pre-primary School) Teachers. Retrieved August 4, 2022, from https://labourmarketinsights.gov.au/occupation-profile/early-childhood-pre-primary-school-teachers?occupationCode=2411

New Zealand Ministry of Education. (2022). Schooling Kaiako/Teacher Turnover Rates. Retrieved July 25, 2022, from https://www.educationcounts.govt.nz/__data/assets/pdf_file/0019/207064/Teacher-Turnover-Indicator-Report-2020.pdf

NSW Department of Education. (2021). NSW Teacher Supply

Strategy. Retrieved from https://education.nsw.gov.au/content/dam/main-education/about-us/strategies-and-reports/media/documents/NSW-teacher-supply-strategy.pdf

O’Flaherty, A. (2021, December 9). Soaring numbers of university students, unregistered teachers fronting classrooms to plug shortages. ABC News. Retrieved from https://www.abc.net.au/news/2021-12-09/preservice-teachers-rushed-through-registration-to-meet-demand/100683334

Queensland College of Teachers. (2021). Queensland College of Teachers response to the Quality

Initial Teacher Education Review.

Rafferty, S. (2022, September 6). Training teachers take up full-time positions to tackle staff shortage in schools. ABC News. Retrieved from https://www.abc.net.au/news/2022-09-06/teacher-shortage-creative-solutions-training-full-time-roles/101406346

Räsänen, K., Pietarinen, J., Pyhältö, K., Soini, T., & Väisänen, P. (2020). Why leave the teaching profession? A longitudinal approach to the prevalence and persistence of teacher turnover intentions. Social Psychology of Education,

23(4), 837–859. https://doi.org/10.1007/S11218-020-09567-X/FIGURES/1

Rorris, A. (n.d.). Impact

of Enrolment Growth on Demand for Teachers: NSW Public Schools to 2031. Retrieved from https://www.nswtf.org.au/files/rorris-report.pdf

Thomson, S., & Hillman, K. (2020). The Teaching and Learning International Survey 2018. Australian

Report Volume 2: Teachers and School Leaders as Valued Professionals (Vol. 2). Canberra: Australian Government Department of Education.

Victorian Department of Education and Training. (2021a). Victorian Teacher Supply and Demand Report

2020: Supplementary data report.

Victorian Department of Education and Training. (2021b). Victorian Teacher Supply and Demand Report

2020.

Victorian Institute of Teaching. (2022). Permission to Teach (PTT) Policy. Retrieved from https://www.vit.vic.edu.au/sites/default/files/media/pdf/2022-04/Policy_VIT_PTT.pdf

Warren, D., & Haisken-Denew, J. P. (2013). Early Bird Catches the Worm: The Causal Impact

of Pre-school Participation and Teacher Qualifications on Year 3 National NAPLAN

Cognitive Tests. Retrieved from http://www.melbourneinstitute.com