The key messages in this Spotlight reveal that:

- Middle leaders are highly regarded educators whose expertise and experience shape teaching quality and student outcomes

- While the roles and responsibilities assigned to middle leaders vary across jurisdictions and schools, most middle leadership roles fall under three broad categories: pedagogical, student-based, and program leadership

- Middle leaders exercise various skills and competencies to fulfil their roles, including leading teaching and learning, collaborating and communicating, and managing and facilitating

- Principal support for middle leaders, including formal role recognition and the provision of professional learning and development opportunities, is crucial to their success

Middle leaders are crucial to the effective functioning of schools and play an important role in shaping student outcomes (Day & Grice, 2019). In recognition of their significance, research exploring middle leadership roles in schools has expanded

rapidly over the past two decades. The term ‘middle leadership’ has been used increasingly in education since emerging in approximately 2005, and by 2016 it had become the predominant term used to describe a range of formal teacher leader

roles, practices, and responsibilities (de Nobile, 2021).

This Spotlight explores the three most common types of middle leadership roles: pedagogical, student-based, and program leadership. Regardless of the type of leadership role they assume, most middle leaders are highly experienced educators who continue

to hold classroom teaching responsibilities alongside their middle leadership role. This “balancing” of roles requires most middle leaders to practice leading teaching and learning, whereby they are both practicing effective teaching in

their own classrooms while supporting their peers to do the same. Middle leaders are also often required to draw on their collaboration, communication, management, and facilitation skills to be effective in their role.

Principal recognition and support for middle leaders is crucial to their success. Principal support, school culture, and formal role recognition all shape the way middle leaders are regarded and influence how their expertise is utilised across their school.

Professional learning and development opportunities can also help middle leaders prepare for the challenges of middle leadership and grow in their role over time.

An opportunity exists for the development of a nationally shared definition of middle leadership and middle leadership standards that reflect the adaptive, relational, and contextual nature of their work. Aspiring and existing middle leaders, principals,

and school communities more broadly will all benefit from an integrated middle leadership framework that supports the development and expertise of this important cohort of leaders.

Middle leaders make up a substantial proportion of the teaching workforce. Estimates suggest one-in-ten members of Australia's teacher workforce hold leadership responsibilities that are distinct from main role leaders (e.g., principals, deputy principals)

(AITSL, 2021). There are approximately 10,000 middle leaders working as assistant principals and head teachers in New South Wales government schools alone (NSW Government, 2022). There is currently no commonly shared or agreed upon definition of middle

leadership in Australia. While principal and deputy principal roles (or equivalent) are commonly recognised school leadership positions, the classification of middle leadership roles and the titles assigned to middle leaders varies between education

systems and sectors. Many schools have also developed their own middle leadership roles and delineate the responsibilities of middle leaders in varied ways (see Table 1).

Table 1. Common middle leadership positions

Jurisdiction

| Formal middle leadership titles in employment agreements | Commonly used middle leadership titles in schools

|

|---|

Australian Capital Territory | Executive teacher

Executive teacher (professional practice)[1] | Director Associate Director |

New South Wales | Assistant principal Assistant principal, curriculum and instruction Head teacher[2] | Director of enrolments Dean of students Dean of teaching and learning Curriculum leader Head of primary Head of secondary Subject coordinator Stage coordinator Wellbeing coach Leader of learning |

Northern Territory | Senior teacher[3] | Head of senior years Head of house |

Queensland | Head of special education Head of department Head of curriculum Literacy/numeracy/pedagogy coach[4] | Year level coordinator

Learning area leader

Curriculum leader

Program leader

Pastoral leader

Dean of teaching and learning

Head of senior school

Head of junior school

Information technology manager

Director of performing arts

Director of sport |

South Australia | Leader[5]

| Coordinator Faculty leader Head of curriculum area Senior leader Senior school leader |

Tasmania | Advanced skills teacher[6] | Head of senior school

Head of middle school

Head of junior school

Head of faculty

Dean of students

Program director

Head of learning |

Victoria | Leading teacher

Learning specialist[7] | Literacy/numeracy specialist

Year level coordinator

Year level leader

Curriculum coordinator

Curriculum leader

Subject area coordinator

Dean of subject/curriculum area

Student services leader |

Western Australia | Senior teacher

Level 3 classroom teacher

Head of learning area[8]

| Head of senior school

Head of junior school

Head of department

Head of subject/curriculum area/learning area |

Overwhelmingly, middle leaders are both classroom teachers and leaders. According to the Australian Teacher Workforce Data (ATWD), at least 91% of middle leaders [9] hold face-to-face teaching roles (AITSL,

2021). In addition to classroom teaching, middle leaders may hold responsibility for a specific curriculum area or year level, (e.g., year coordinator, subject coordinator, head of department, head of year). Alternatively, they might lead strategy

and development across the school within a particular focus area (e.g., director of curriculum, head of digital learning and practice, director of pastoral care). Some middle leaders may also hold important line management duties. Mechanisms such

as feedback, performance and development processes, professional development planning, and mentoring of new staff enable these middle leaders to effect change in the classroom and impact on the quality of teaching across their school.

While the terms used to refer to middle leaders may be different, the responsibilities allocated to them reveal many similarities. Middle leadership roles in Australian schools can be loosely divided into three different categories: pedagogical leadership,

student-based leadership, and program leadership.

Pedagogical leadership

Pedagogical leadership is used here to refer to middle leadership roles that focus on pedagogical practices and student learning within or across curriculum areas. Head of department, head of learning area, and curriculum coordinator are some examples

of pedagogical leadership roles at the middle leader level. Middle leaders in these roles are often required to set and model pedagogical practices within their learning area of responsibility (Grootenboer et al., 2019). Pedagogical leadership also

encompasses instructional leadership, which is about supporting classroom teachers to implement curriculum (Abel, 2016). Middle leaders with pedagogical leadership responsibilities are often required to implement and monitor quality improvement processes

and conduct analyses of student data to understand and evaluate the effectiveness of learning programs (Grootenboer, 2018). Middle leaders in these roles are often required to be aware of new standards and best practice and understand how these can

be integrated into their school’s day-to-day teaching and learning processes.

Effective pedagogical leadership at the middle leader level is crucial to improving teaching and learning outcomes. A synthesis of 42 studies exploring department-head contributions to secondary school improvements found that department-head leadership

has a greater influence on student learning than whole-school factors and school-leader influences (Leithwood, 2016). The research synthesis suggested that meaningful pedagogical leadership is fostered through a collegial school-wide culture, a particularly

strong school-wide emphasis on teaching and learning, and whole-school agreement on the importance of students, their learning, and their wellbeing. The inclusion of student voice in decision-making processes and the systematic use of student data

to inform instructional improvements also foster effective department-head leadership (Leithwood, 2016). Pedagogical leadership is multifaceted and requires middle leaders to draw on a variety of management and leadership skills, with the ultimate

aim of strengthening teaching practices and improving student outcomes.

The Curriculum Area Middle Managers (CAMMs) model

The CAMMs model posits that middle leaders who hold leadership responsibilities at the curriculum area level usually hold four different leadership roles (White, 2001). They operate as instructional leaders, with responsibility for classroom teaching

and learning, professional development, and accountability. They also work as learning area architects, with responsibility for student management, teacher support, learning area staff management, communication, representation, and culture. They

are also often required to be curriculum strategists, with responsibility for vision-setting and curriculum direction. Lastly, they are administrative leaders, which captures more traditional managerial responsibilities such as budgeting, documenting,

and resourcing (White, 2001).

Middle leaders make up a substantial proportion of Australia’s teaching workforce.

Middle leaders make up a substantial proportion of Australia’s teaching workforce.Student-based leadership

While almost all middle leaders spend at least some of their week in a student-facing role (AITSL, 2021; de Nobile & Ridden, 2014; Lipscombe et al., 2020), some middle leadership roles demand more contact with students than others. Examples of student-based

middle leadership roles include head of year, year level coordinator, and Dean of students. While all middle leaders are, of course, working towards supporting student outcomes, student-based middle leaders are often focused on the social development

and day-to-day wellbeing of a specific cohort of students. Concerns around student welfare, pastoral care, behaviour and attendance are especially relevant to these types of middle leaders (Lipscombe et al., 2020). Student-based leadership roles are

especially important for learners as they can serve as a first point of call for students when they have an issue or concern.

Middle leaders holding student-based leadership roles play an important role in supporting student’s learning and personal development outcomes. These middle leaders might triangulate student data to understand the impact of students’ personal

circumstances and behaviours on their attendance, classroom engagement, and learning outcomes more broadly. They might work directly with students to address these issues or manage school staff who have accountabilities and expertise in these areas.

These middle leaders will often be responsible for leading implementation of student-based engagement approaches and mentoring other staff to recognise and address indicators of student wellbeing.

In some schools, heads of year (and equivalent roles) move through each year level with the same cohort of students. This enables the middle leader to develop a deep understanding of the students over time, including their dynamics, personalities and

individual circumstances. The students then benefit from the highly personalised support and guidance provided by this type of middle leader.

Program leadership

Middle leaders with program leadership responsibilities take ownership over specific initiatives or focus areas across their school. These roles increasingly encompass both academic and non-academic streams of work (Andrews & Hooley, 2017; Woo, 2020).

Rather than working closely with a particular cohort of students, such as a year level, middle leaders in these positions often provide support to students across the school. Examples of program leadership roles include head of student wellbeing,

religious education coordinator, director of performing arts, and sports coordinator. Their expertise in a specific area or program enables them to provide highly effective support and enriched learning experiences to students (Bryant & Walker,

2022).

Many extra-curricular and wellbeing programs aim to support students’ engagement in their learning and, by extension, their learning outcomes. Middle leaders with program leadership responsibilities will often collect and analyse data in order to

understand and demonstrate the impact school-based programs are having on students and their learning and/or wellbeing outcomes. In schools with larger programs or departments comprising multiple staff, these middle leaders may also hold supervisory

responsibilities and manage performance and development processes and associated activities.

The establishment of middle leadership roles encompassing program leadership portfolios is highly responsive to policy changes and developments in education. For example, the prevalence of school-based ICT coordinators has been growing over the past 20

years, driven by the integration of ICT into teaching and learning (León-Jariego et al., 2020). Similarly, efforts to strengthen the provision of mental health support to children and young people has driven an increase in the prevalence of

mental health and wellbeing coordinator roles across Australian schools (Darling et al., 2021).

Middle leadership roles are often established in response to the characteristics and requirements of the school community. This does not mean, however, that middle leaders use different practices in every different context. Effective middle leaders are

responsive to context and tailor their leadership practices based on their school’s needs. Middle leading is an adaptive practice that draws on a broad set of skills and capabilities. Noting that these skills and capabilities can be grouped

or labelled in several different ways, research has emphasised three broad categories of practice: leading teaching and learning; collaborating and communicating; and managing and facilitating (Grootenboer, 2018).

Leading teaching and learning

Middle leaders are often involved in decision-making conversations alongside school leaders and other staff. Their (often) ongoing teaching experience gives them a unique understanding of the realities and complexities of implementing various decisions,

and their simultaneous engagement in leading and teaching is an asset that can strengthen decision-making processes (Grootenboer et al., 2021). Middle leaders’ influence and authority enables them to shape school policy and programs, while also

supporting school staff through supervision and management practices (Bennett et al., 2007; de Nobile, 2021; Grootenboer, 2018; Hirsh & Bergmo-Prvulovic, 2019).

Middle leaders are expected to lead, promote and sustain effective practices to support student learning outcomes and provide high-quality teaching within their own classrooms, while often “simultaneously being a mentor, coach, supporter and evaluator

for their colleagues” (Davies, 2020). In maintaining high quality teaching and learning in their own classrooms, and demonstrating these practices to others, middle leaders are well-positioned to support and mentor other teachers to strengthen

their own teaching practices. Specific leading teaching and learning practices for middle leaders include:

- Modelling quality teaching and learning

- Delivering professional learning

- Supporting teachers to engage in new pedagogical practices

- Leading curriculum delivery and/or advising on curriculum delivery approaches

- Leading development of assessments and/or assessment strategies, and moderating assessments

- Observing lessons and providing expert mentoring, feedback, and goal setting

- Demonstrating strong pedagogical and curricula knowledge and modelling continuous learning themselves

Collaborating and communicating

Communication and collaboration are routine parts of any leadership role. Middle leadership specifically has been described as a sort of conduit of pedagogical and professional capital between senior leaders and teaching staff, where the success of the

role hinges on high levels of trust, strong relationships, and willingness to compromise (Branson et al., 2016).

Middle leaders may communicate “upwards” in order to share information and feedback with school leaders, and communicate “downwards” to distribute and allocate tasks from the school executive (Bennett et al., 2007). They will often

lead the collegial development of ideas, discussions of practice, and facilitation of critical professional dialogue through professional learning communities (Grootenboer, 2018).

Middle leaders will often be required to communicate with members of their broader school community and beyond, including parents and system and sector representatives (Flückiger et al., 2015). Regardless of the specific context, middle leaders may

use the following practices to collaborate and communicate effectively:

- Creating practice arrangements for developing and sharing teaching practice

- Cultivating cultures of collegiality

- Developing and sustaining relational trust

- Serving as 'bridge', 'broker' and 'buffer' between teaching colleagues and senior leaders

- Purposefully adapting different ways of knowing and working

- Reporting to parents and liaising with the wider school community, including ensuring transparency, accuracy, confidentiality, fidelity and inclusion in reporting

Managing and facilitating

Middle leaders are often required to undertake various administrative and managerial functions. These tasks often involve the development and maintenance of policies and procedures that support the more collaborative and student-focused aspects of their

role (de Nobile, 2021). While some of these practices may appear highly administrative, such as developing processes and procedures, they are crucial to promoting collegiality and a culture of transparency within teaching teams. Specific middle leader

practices include:

- Organising and facilitating professional learning and development opportunities

- General professional development and performance development planning with staff, including mentoring new staff and developing underperforming staff

- Negotiating conditions and resources for staff development

- Coordinating time for classroom visits, collaboration, reflection, and meetings with and between colleagues

- Translating whole school initiatives into meaningful and achievable team goals

- Providing opportunities for teachers to develop leadership practices themselves

- Developing procedures and systems that facilitate data collection and analysis, record-keeping, information-sharing and ongoing monitoring and evaluation to inform improvements in teaching and learning

Administrative burden can become an overwhelming component of middle leadership roles (Lipscombe et al., 2020). Furthermore, the positioning of middle leaders “in between” teaching staff and clearly defined school leaders, such as principals,

means that their roles can become blurred as they straddle involvement in whole-school issues and responsibility for more discrete, specific areas. When they are fully supported in well-defined, delineated roles and given access to relevant professional

learning and development, middle leaders can maximise their impact on effective teaching and learning within their school (Flückiger et al., 2015).

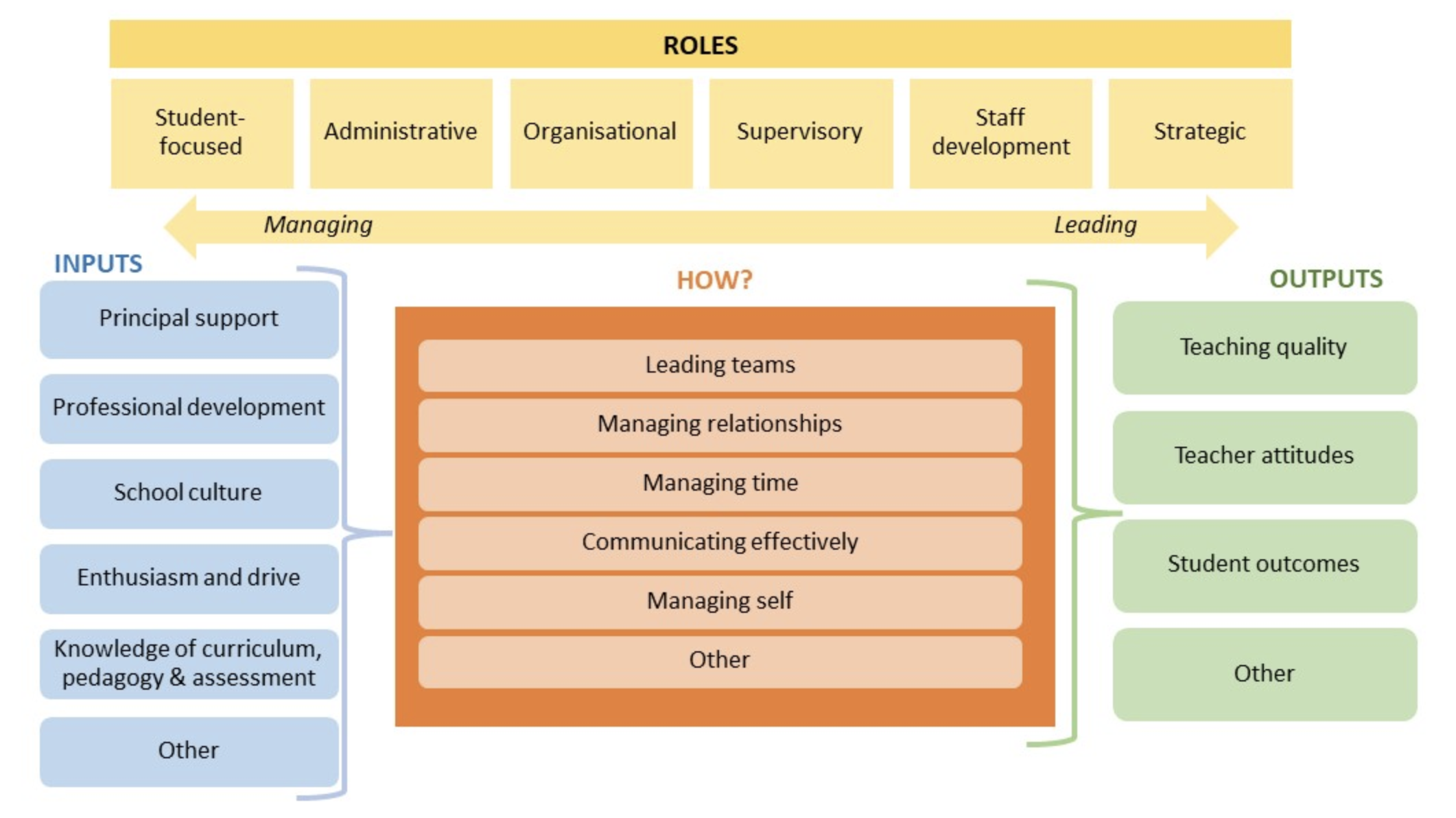

The Middle Leadership in Schools model

Many of the practices and responsibilities of the middle leader have been linked together in the Middle Leadership in Schools (MLiS) model, which offers a useful visual representation of the supports middle leaders require, common practices they use to

enact their roles, and the outputs they can positively influence through their roles (de Nobile, 2018).

The MLiS model was developed through an extensive review of existing literature and distinguishes between ‘what’ middle leaders do and ‘how’ they do it (see Figure 1) (de Nobile, 2018).

The model identifies five factors or inputs that are required for middle leaders to be effective in their roles: principal support; school culture; professional development; knowledge of curriculum, pedagogy and assessment; and enthusiasm and drive. While

the literature on middle leadership most commonly highlights the importance of principal support, all these factors can help to facilitate success for middle leaders, and, conversely, middle leaders may struggle to be effective without these inputs.

The model divides the roles middle leaders usually hold into two categories. ‘Managing’ roles encompass student-focused roles, administrative roles, and organisational roles. These roles are often focused on developing processes and ensuring

organisation within the school. ‘Leading’ roles, on the other hand, comprise supervisory roles, staff development roles, and strategic roles. These roles often aim to motivate others within the school and to improve or change practice

through influence (Grootenboer et al., 2021).

The MLiS model highlights the various strategies middle leaders use to enact their roles, including managing relationships, leading teams, communicating effectively, managing time, and managing self. When they are properly supported in their roles, middle

leaders can have positive impacts on various outputs including teaching quality, teacher attitudes, and student outcomes.

Figure 1. The Middle Leadership in Schools model (de Nobile, 2018)

Common middle leadership tasks

A recent survey exploring formal middle leadership roles in New South Wales government schools revealed that middle leaders engage in a variety tasks (see Table 2). Middle leaders’ reported tasks were organised into seven themes, which together

highlight the diversity of responsibilities middle leaders hold: developing staff, student-focused, administrative, organisational, curriculum-centred, supervising staff, and leading learning and change (Lipscombe et al., 2020). These findings

reveal that middle leaders spend most of their time working directly with students. When they are not with students, they are most commonly supervising the work of other teachers and using data to monitor impact and improve teacher practice.

Table 2. Most commonly reported tasks middle leaders undertake in NSW government schools (n=2,608)

Middle leadership tasks by theme |

|---|

1. Helping students (student-focused) |

2. Supervising staff in a year/grade or stage (supervisory)

|

3. Supervising staff members (supervisory) |

4. Being responsible for records of student behaviour, academic progress or other student data (administrative) |

5. Dealing with student behaviour (student-focused) |

6. Creation and/or maintenance of records relating to student behaviour, achievement or other student data (administrative) |

7. Implementing curriculum (organisational) |

8. Creation and/or maintenance of information/data relating to student progress (administrative) |

9. Organising a team or committee (organisational) |

10. Mentoring staff members (staff development) |

11. Monitoring the performance of staff (supervisory) |

12. Helping staff members with aspects of their work (staff development) |

Middle leaders are highly experienced educators. They are often promoted to their role because they have demonstrated effective teaching practice and hold significant experience and expertise (Grootenboer et al., 2021). The average middle leader

first entered the teaching profession 22 years ago and worked as a classroom teacher for 11 years before becoming a middle leader (ATWD, 2021). Findings from a survey of educators holding formal middle leadership roles in New South Wales government

schools also demonstrated the majority (71%) of middle leaders have at least 10 years of teaching experience (Lipscombe et al., 2020). However, male educators are, on average, promoted to leadership roles more quickly than their female counterparts

(1.9 years earlier for middle leadership roles). While the majority of Australia’s teaching workforce is female (78%), men are slightly over-represented at all levels of leadership, including middle leadership roles (33% male, 67% female)

(AITSL, 2021).

While jurisdictions and education settings demarcate formal middle leadership roles differently, schools also tailor middle leadership roles and structures to meet their own needs. Research conducted with schools in England has demonstrated that

the average number of middle leaders increases with school size (defined in terms of student enrolment) (Stokes et al., 2019). In Australia, secondary schools, combined schools and special schools have a higher proportion of leaders than primary

schools. This can be partly explained by subject specialisations in secondary education and the resulting need for faculty leaders or heads of department (AITSL, 2021).

Like all members of Australia's teaching workforce, middle leaders are dedicated and hard-working educators. According to the ATWD, middle leaders work 57.4 hours per week, which is slightly more than classroom teachers (56.2 hours), and slightly

less than principals (61.3 hours) or deputy principals (60 hours). Middle leaders report working fewer face-to-face teaching hours per week (16.6 hours; 29% of their time) than classroom teachers (25.5 hours; 46% of their time), but more than

principals (5.5 hours; 9% of their time) and deputy principals (11.3 hours; 19% of their time) (AITSL, 2021). This is unsurprising, given that middle leaders are generally afforded release time to fulfil their leadership responsibilities.

The release time allocated to middle leaders varies based on their role in the school and school leadership preferences, while requirements differ across jurisdictions, systems and sectors. While the majority of Australia’s middle leaders

are employed to work full-time (80% full-time, 20% part-time), they are more likely to work part-time than principals (4% part-time) and deputy principals (16% part-time) (AITSL, 2021).

The Australian Teacher Workforce Data (ATWD)

The ATWD unites and links data on initial teacher education and the teacher workforce to build a national picture of Australia's teaching profession. Understanding

the career paths and work experiences of teachers across Australia is a major part of the ATWD. Future waves of the ATWD will continue to develop and inform our understanding of leadership roles, including middle leadership roles, across

Australian early learning services and schools. By completing the annual ATWD Teacher Survey as a teacher you are contributing to this

initiative and helping create a clearer picture of the profession.

An opportunity exists to develop a nationally shared definition of middle leadership and middle leadership standards that reflect the adaptive, relational, and contextual nature of their work.

An opportunity exists to develop a nationally shared definition of middle leadership and middle leadership standards that reflect the adaptive, relational, and contextual nature of their work.Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people are under-represented across Australia’s teacher workforce. Estimates suggest fewer than 1% of school leaders, and only 1-2% of teachers, identify as Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander. The

number of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander educators has not kept up with the growth in the number of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander students (6.2%) (Australian Bureau of Statistics, 2022).

Increasing Indigenous representation at the classroom teacher level will help to create a pipeline of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander middle and school leaders. Succession planning, including in remote majority-Indigenous schools which often

experience high levels of teacher and school leader turnover (Hall, 2012), could also help to address the under-representation of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander middle and school leaders in Australian schools (White et al., 2013).

Diversity in school leadership

You can read more about the diversity of Australia's school leaders in a previous Spotlight edition, Diversity in school leadership.

Effective leadership in schools is rarely left to chance alone. Middle leadership can be purposefully fostered, cultivated, and developed. Principal support is one of the most significant contributors to the success of middle leaders (Gurr

& Drysdale, 2013). Principals build school culture and model the way other school staff should regard middle leaders and their expertise (Hirsh & Segolsson, 2019). In providing opportunities for middle leaders to engage in professional

learning and development, principals can communicate the value they place in these roles and their ambition for their middle leaders to succeed. Ongoing professional learning provides important opportunities for reflection and the development

of skills and knowledge at any teacher career stage.

Middle leaders engage in professional learning through a variety of means. More structured activities include professional development events such as workshops and conferences, while on-the-job learning opportunities often involve collaborative

learning from peers. According to the ATWD, the amount of professional learning educators undertake increases with seniority. Middle leaders report spending more time engaged in professional learning activities over the course of a year

(46.3 hours) than teachers with leadership responsibilities (42.6 hours) and classroom teachers (38.7 hours). However, this is considerably less than the amount of time principals (73.4 hours) and deputy principals (55.6 hours) report

spending engaged in professional learning (AITSL, 2021).

The most effective professional learning for middle leaders is structured and highly relevant to their role (Bryant & Walker, 2022). Although middle leaders report that their professional development experience is valuable, their perceptions

are slightly lower than principals’ (AITSL, 2021). Specifically, they are less likely than principals to agree that: their professional learning was aligned to their own professional development needs (81% vs 89%); that it was aligned

to the needs of their education setting (88% vs 92%); that they have had opportunities to implement what they had learned (78% vs 88%); and that they have had opportunities to reflect on or evaluate the impact their professional learning

has had on learners (61% vs 82%) (AITSL, 2021). Various jurisdictions and professional bodies have developed structured professional learning programs especially for middle leaders. These are outlined below.

Resource list: Professional development programs for middle leaders

The Victorian Academy of Teaching and Leadership's Create: Middle Leaders is a six-month

program that aims to strengthen middle leaders' abilities to lead teams in order to improve student wellbeing, to encourage students to be engaged in their learning, and to help them achieve their best.

The New South Wales Government's School Leadership Institute hosts the Middle Leadership Development Program,

which is designed to build leadership excellence and help lift learning outcomes across the state. The Institute also offers Middle Leaders Online Induction for newly appointed, first-time substantive or long-term relieving assistant

principals and head teachers. Aspiring middle leaders are also welcome to participate.

The Queensland Education Leadership Institute (QELi) offers the Leadership for Middle Leaders Online Program in partnership with the Australian Council for Educational Leaders (ACEL). The program explores the knowledge, skills and confidence middle leaders need to lead and develop others to achieve effective leadership of school communities.

Candidates for leadership roles in rural and remote Queensland schools can participate in the Take the Lead program through

one of three strands - aspiring small school principals, aspiring associate leaders, or aspiring large school principals.

The Tasmanian Government's Professional Learning Institute runs a Middle Leaders in Schools program through a blended learning approach. The program aims

to build middle leader's capabilities, skills, and confidence.

Catholic Education South Australia and the National Excellence in School Leadership Institute have partnered to deliver the Catholic Schools Middle Leadership Program. It

focuses on strengthening middle leaders' abilities to engage learners and promote learner agency, create effective learning designs, build learning communities, and lead for sustainability and change.

The Association of Independent Schools of New South Wales offers Leading from the Middle,

which is designed to increase the capacity and internal coherence of middle leadership teams so they can become more effective.

Independent Schools Victoria offers Leading from the Centre 2.0, a professional learning program for middle leaders, senior leaders and principals that can be tailored

to meet the unique needs of each school.

Highly Accomplished and Lead Teacher (HALT) certification

In addition to the programs outlined above, HALT certification enables the recognition and promotion of quality teaching and leadership. HALT certification provides opportunities for expert teachers, including middle leaders, to reflect

on and develop their professional practice. You can find out more about HALT certification here.

Middle leaders play a pivotal role in supporting teacher quality, teacher attitudes and student outcomes. Both inside and outside of the school gates, there is a strong understanding that middle leaders have a significant impact on teaching

practices and learning outcomes. Middle leaders and middle leadership practices have become increasingly recognised as significant factors in the success of Australian schools.

A growing body of research has highlighted the importance of understanding these practices and ensuring optimal conditions for middle leaders to develop and lead effectively. Ongoing attempts to delineate middle leader roles and demonstrate

their significance have also highlighted challenges in role clarity and difficulties in comparing middle leaders across different jurisdictions, sectors, and settings. The research included here demonstrates that while the terms used to

refer to middle leaders may differ, middle leaders utilise a common set of skills and competencies. An opportunity now exists to develop a nationally shared definition, and middle leadership standards that reflect the adaptive, relational,

and contextually informed nature of middle leaders’ work.

In October 2022, the Queensland Department of Education partnered with AITSL to develop standards for middle leaders, aligned with the Australian Professional Standard for Principals.

Abel, M. (2016, April 25). Why Pedagogical Leadership? McCormick Center for Early Childhood Leadership at National Louis University. https://mccormickcenter.nl.edu/wp-content/uploads/2018/03/4-25-16_WhyPedagogicalLeadership.pdf

AITSL. (2021). Australian Teacher Workforce Data: National Teacher Workforce Characteristics Report. https://www.aitsl.edu.au/docs/default-source/atwd/national-teacher-workforce-char-report.pdf?sfvrsn=9b7fa03c_4

Andrews, D., & Hooley, T. (2017). ‘ … and now it’s over to you’: recognising and supporting the role of careers leaders in schools in England. British Journal of Guidance and Counselling, 45(2), 153–164.

https://doi.org/10.1080/03069885.2016.1254726

Australian Bureau of Statistics. (2022). Schools. https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/people/education/schools/2021

Bennett, N., Woods, P., Wise, C., & Newton, W. (2007). Understandings of middle leadership in secondary schools: a review of empirical research. School Leadership and Management, 27(5), 453–470. https://doi.org/10.1080/13632430701606137

Boylan, M. (2018). Enabling adaptive system leadership: Teachers leading professional development. Educational Management Administration & Leadership, 46(1), 86–106.

Branson, C. M., Franken, M., & Penney, D. (2016). Middle leadership in higher education: A relational analysis. Educational Management Administration & Leadership , 44(1), 128–145.

Bryant, D. A., & Walker, A. (2022). Principal-designed structures that enhance middle leaders’ professional learning. Educational Management Administration and Leadership. https://doi.org/10.1177/17411432221084154

Darling, S., Dawson, G., Quach, J., Smith, R., Perkins, A., Connolly, A., Smith, A., Moore, C. L., Ride, J., & Oberklaid, F. (2021). Mental health and wellbeing coordinators in primary schools to support student mental health: protocol

for a quasi-experimental cluster study. BMC Public Health, 21(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-021-11467-4

Davies, J. (2020, February 26). Supporting school middle leaders. The Association of Independent Schools of NSW. https://www.aisnsw.edu.au/newsroom/?ArticleId=bfd68db2-c9bf-463a-9219-179a33037ed5

Day, C., & Grice, C. (2019). Investigating the Influence and Impact of Leading from the Middle: A School-based Strategy for Middle Leaders in Schools. https://www.aisnsw.edu.au/Resources/WAL%204%20%5BOpen%20Access%5D/Leading%20from%20the%20Middle%20-%20A%20School-based%20Strategy%20for%20Middle%20Leaders%20in%20Schools%20-%20Full%20Report.pdf

de Nobile, J. (2018). Towards a theoretical model of middle leadership in schools. School Leadership and Management, 38(4), 395–416. https://doi.org/10.1080/13632434.2017.1411902

de Nobile, J. (2021). Researching Middle Leadership in Schools: The State of the Art. International Studies in Educational Administration, 49(2), 3–27.

de Nobile, J., & Ridden, P. (2014). Middle leaders in schools: Who are they and what do they do? Australian Educational Leader, 36(2), 22–25. https://doi.org/10.3316/aeipt.203429

Flückiger, B., Lovett, S., Dempster, N., & Brown, S. (2015). Middle Leaders: Career pathways and professional learning needs. Leading & Managing, 21(2), 60–74. http://hdl.handle.net/10072/341889http://www.acel.org.au/acel/ACELWEB/Publications/Leading___Managing.aspx

Grootenboer, P. (2018). The practices of school middle leadership: leading professional learning. Springer Singapore.

Grootenboer, P., Edwards-Groves, C., Attard, C., & Tindall-Ford, S. (2021). Middle Leaders are not just Principals-in-waiting. Australian Educational Leader, 43(3), 41–43. https://doi.org/10.3316/INFORMIT.114978398070670

Grootenboer, P., Edwards-Groves, C., & Rönnerman, K. (2019). Understanding middle leadership: practices and policies. In School Leadership and Management (Vol. 39, Issues 3–4, pp. 251–254). https://doi.org/10.1080/13632434.2019.1611712

Gurr, D., & Drysdale, L. (2013). Middle‐level secondary school leaders: Potential, constraints and implications for leadership preparation and development. Journal of Educational Administration, 51(1), 55–71.

Hall, L. (2012). The ‘Come and Go’ syndrome of teachers in remote indigenous schools: Listening to the perspective of indigenous teachers about what helps teachers to stay and what makes them go. Australian Journal of Indigenous Education, 41(2),

187–195. https://doi.org/10.1017/jie.2012.13

Hirsh, Å., & Bergmo-Prvulovic, I. (2019). Teachers leading teachers–understanding middle-leaders’ role and thoughts about career in the context of a changed division of labour. School Leadership and Management, 39(3–4),

352–371. https://doi.org/10.1080/13632434.2018.1536977

Hirsh, Å., & Segolsson, M. (2019). Enabling teacher-driven school-development and collaborative learning: An activity theory-based study of leadership as an overarching practice. Educational Management Administration & Leadership, 47(3),

400–420.

Leithwood, K. (2016). Department-Head Leadership for School Improvement. Leadership and Policy In Schools, 15(2), 117–140.

León-Jariego, J. C., Rodríguez-Miranda, F. P., & Pozuelos-Estrada, F. J. (2020). Building the role of ICT coordinators in primary schools: A typology based on task prioritisation. British Journal of Educational Technology, 51(3),

835–852. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjet.12888

Lipscombe, K., de Nobile, J., Tindall-Ford, S., & Grice, C. (2020). Formal Middle Leadership in NSW Public Schools. https://education.nsw.gov.au/teaching-and-learning/school-leadership-institute/research/middle-leadership

NSW Government. (2022, September 13). Middle Leader Role Description released. https://education.nsw.gov.au/teaching-and-learning/school-leadership-institute/latest-news/mlrd-release

Stokes, L., Bryson, A., & Wilkinson, D. (2019). What does leadership look like in schools and does it matter for school performance? IZA - Institute of Labor Economics Discussion Paper Series, 12580.

White, N., Watkin, F., Nobin, K., Mcginty, S., Frawley, J., & Bezzina, M. (2013). Leadership and Leadership Succession for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Schools: a review of the literature. Journal of Australian Indigenous Issues, 16(2),

36–52.

White, P. (2001). The Leadership of Curriculum Area Middle Managers in Victorian Government Secondary Schools. Leading & Managing, 7(2), 131–150. https://doi.org/10.3316/aeipt.123515

Woo, D. (2020). The leadership of ICT coordinators: A distributed perspective. Educational Management Administration and Leadership, 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1177/1741143220979714