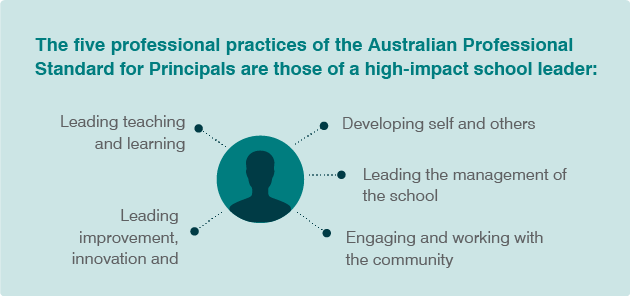

High-impact leadership:

- creates the conditions for teachers to understand their impact on learner outcomes and continually improve their practice

- operates in fast-changing and increasingly complex circumstances

- understands the strong foundations of a great education

- uses educational expertise and management skills to create a school culture focused on improving the quality of teaching and learning to lead to progress for all learners

- fosters a culture of professional learning and growth, where staff work together to develop and share expertise.

High-impact leadership is most effective when leadership is distributed and collaborative, and when teams work together to accomplish the shared vision and aims of an education setting. A high-impact leader will evolve their practice and capabilities

as they evolve through their career.

What needs to be considered?

- The most effective leaders see learning as central to their professional lives.

- Almost all successful leaders draw on the same core leadership practices and behaviours.

- Personal qualities and capabilities explain the significant variation in leadership effectiveness.

Reflection

Consider the scenarios below to gauge your progress and growth towards leading for impact. Although this tool has been designed for leaders, teachers may also consider the questions in relation to their education setting practices.

Scenarios | Does this sound like your education setting? |

|---|

Staff independently seek out others to grow expertise. Outside of formal expectations, teachers set up informal coaching relationships and schedule sharing sessions. | Refer to Creating a safe environment for risk taking in learning |

There is a culture of professional growth. Staff openly discuss mistakes and challenges and feel safe to ask for help. Teachers share goals and celebrate achievements. | Watch Building a culture and cycle - Australind Senior High School, WA |

Learner outcomes are at the centre of the culture. Evidence is referenced in discussions, decisions, and planning. Evidence is used to consider if new programs will target learner needs. | Read InSights: Literature review: A culture of trust enhances performance |

The vision of the education setting is explicit, understood and shared. It is displayed and referred to regularly. Leaders remind staff of the vision in meetings and it appears on shared documents. | Explore Leadership Scenarios |

Leadership is distributed across all staff, with teachers owning and contributing to initiatives across the organisation. Emerging leaders are approached and encouraged to collaborate with leaders and teams to accomplish

goals. | Explore Coach others |

Staff have opportunities to develop their understanding of their own impact. Staff meetings are set up to engage with evidence so teachers can safely reflect on and adjust their teaching practice. | Refer to Module 3b |

The responsibility of teaching and learning is genuinely shared between teachers, leaders and learners. Reflective practices consider how planning and policy work supports quality teaching. When evidence suggests a

deficit, consideration is given to . | Explore Build a professional growth culture |

Leaders are challenged to grow and evolve across all stages of their career. Support provided by the education setting is targeted to the leader’s learning stage. There is a clear progression in goals set by

leaders. | Explore Build a professional growth culture |

Leaders are committed to learning about and acting on culturally responsive pedagogies and improvement processes with staff. | Explore Culturally responsive teaching resources |

Mentors are skilled teachers, leaders or educators committed to supporting another teacher. A skilled teacher is not defined necessarily by years of experience, but by learner outcome success.

The role of a mentor is to work with their mentee and support them towards a professional goal. A mentor may:

- provide advice and help the mentee resolve issues they are facing

- model different teaching strategies

- observe the mentee and provide constructive and meaningful feedback

- check in on the wellbeing of the mentee and provide emotional support.

Tips for mentors

- establish a set of goals to track through the relationship

- mentees should leave each session with at least one action

- connect your mentees with teachers in expertise in other areas

- set aside dedicated, privileged time for mentoring

Mentees are often beginning teachers but can also be experienced teachers looking to learn from a colleague.

Beginning teachers working at the Graduate career stage can work with a mentor to help them move to full registration.

A mentor’s practice and experience should align with the specific growth areas a mentee is working on.

Tips for mentees

- prepare for mentoring meetings through active reflection, a list of recent achievements and an area for guidance

- regularly review your goals to stay on track

- be honest and open with your mentor about any issues

- understand the purpose of feedback, so you don’t find it confronting

- find someone you respect and can build a rapport with

A starting point for the mentoring relationship can simply be how mentees are feeling or managing at that point in time, with a next step: even if that is just a plan to meet again and continue the discussion.

Most jurisdictions and regulatory bodies have established mentoring programs for new teachers, but some teachers face barriers to access.

Remote coaching offers a “safe zone” where early career teachers can openly ask questions without fear of judgment.

Teachers who are in remote locations, or are the only teacher of their kind in their context, also find online mentoring beneficial.

Working online requires planning as it is not as straightforward as working with a colleague in the same location. As remote mentoring allows mentees to connect with mentors anywhere, mentees can be more deliberate in planning and, searching for mentors:

- in a similar context – regional/rural/metropolitan

- of a specific year level

- in a specific subject area

- with a similar background/lived experience

Before beginning, mentors and mentees need to identify and agree on the medium they will use, then spend some time getting familiar with the app/technology. While this seems obvious, frustration with technology while learning something new can limit engagement.

There are some aspects of mentoring that require special consideration, so they are not lost through mentoring online.

Potential problem | Potential solution |

|---|

the mentor is unable to observe the mentee’s practice | the mentee records themselves teaching and sends the recording to their mentor |

the mentee doesn’t have access to the mentor for informal feedback or advice | establishing five-minute check in times between meetings where the mentee can ask any urgent questions |

the mentor can’t informally check in with their mentee’s colleagues and students. | development of student feedback surveys or 360˚ surveys, with results shared with the mentor |

Reflection

Identify examples of mentoring in your education setting.

Examples of mentoring practices | What does it look like? | What are the benefits to teachers and students? |

|---|

Supervising pre-service teachers Assisting with National certification Mentoring graduate teachers Mentoring teaching staff Mentoring emerging leaders Remote mentoring | | |

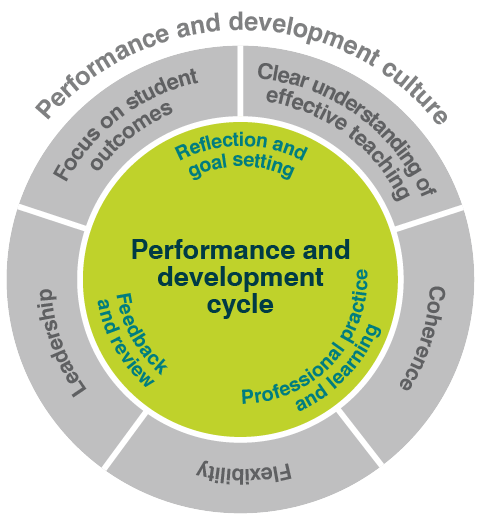

Performance and development is a continuous cycle. Teachers and leaders work together to establish goals and learning opportunities, monitor and evidence progress, and provide formal and informal feedback and recognition for achievement.

Research shows that leaders who embrace learning as a foundational aspect of the development cycle for both teachers and students have a positive impact on outcomes. To become a ‘Learning Leader’, leaders must:

- be learning and developing as individuals,

- set optimal conditions for others to keep learning.

Learning leaders who consider the impact of emotions on how teachers approach their work are more likely to grow a culture where all learners can safely take risks to develop. Experienced teachers know the power of emotions in the classroom, but emotions

can be overlooked, with more emphasis placed on learning theory and cognitive processes (Newberry, Gallant & Riley 2013).

Adequate training for leaders in how to look after themselves, teachers and students during moments of intensity is necessary to deal with strong emotions when they inevitably arise in learning contexts.

The way that leaders position themselves will establish safety for others to take learning risks (Bowlby 1988), provide opportunities for learning, and then consolidate these connections over months of repeated use (Doidge 2007).

School leaders need to:

- act rationally in emotional situations; expressing emotions calmly and constructively

- take action to look after their physical, mental, emotional and spiritual wellbeing

- prioritise constant numerous pressing priorities and conflicting demands

- take appropriate action in times of uncertainty in the areas that are within their control

- look for and focus on the positives in situations and people, without ignoring the negatives.

Modelling learning leadership involves understanding the role of professional capital in education settings. According to Hargreaves and Fullan (2012) the sum of a culture of learning and improvement can be labelled ‘professional capital’.

Professional capital is derived from:

- human capital: the knowledge, skills, information and learning individuals bring to a group through education and training

- social capital: collaborative culture, interactions and social networks, teamwork, trust, commitment and relationships

- decisional capital: the collaborative capacity to make decisions

An individual high in human capital working in a school of low social capital will ‘either leave or burnout’, whereas a school with high social capital ‘generates increased human capital’ (Hargreaves & Fullan 2012).

The Gonski panel (2011) recommended that ‘Australian teachers and school leaders, and those who determine policy and make decisions in schools, sectors and systems, [need] to take responsibility for their own learning and to commit to building a

purposeful, active and pervasive learning culture in every school and workplace’.

Leaders who design learning experiences that meet the developmental needs of teachers have greater impact. A differentiated approach to staff development that considers specific contexts is most effective.

For example, a beginning teacher has very different growth requirements to their colleague with five years’ experience. Generally, the former needs coaching while the latter will benefit more from mentoring.

Professional conversation

Using the SWOT chart below, discuss with a colleague.

SWOT analysis | Creating a safe environment for risk taking | Understanding professional capital | Designing and refining evolving learning experiences |

|---|

S = Strengths | | | |

W = Weaknesses | | | |

O = Opportunities | | | |

T = Threats | | | |

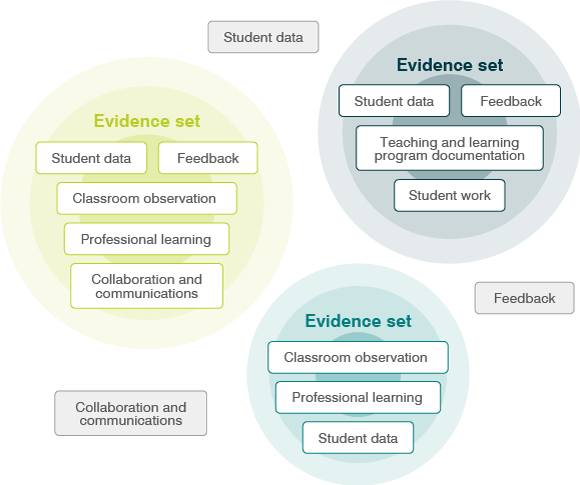

Evidence is a crucial component in effective teaching. Quality teaching practices use sets of evidence that include a range of artefacts to strengthen their reliability. Leaders can encourage teaching staff to consider their impact by evaluating what

the evidence says about their teaching practice, measuring this with reference to their goals and the Standards.

Ways to support teachers to use evidence to demonstrate proficiency:

- practice-focused mentoring

- support implementation of teaching evaluations/observations

- ensure the performance and development process uses evidence in an effective way

Practice-focused mentoring supports the professional development of teachers through ongoing observation, conversations, evidence about and assessment of practices, goal setting aligned with standards of quality teaching, and technical and emotional support

(Achinstein & Villar 2004).

Practice-focused mentoring improves knowledge and skill, allows for engagement with evidence, supports other strategies such as feedback and participation in professional networks, and reinforces that a commitment to improvement should be embedded in

daily practice.

Mentors can use the relationship they have with teachers as an opportunity to engage with evidence, examining how evidence speaks to the teacher’s goals and the impact on learner outcomes.

Practice-focused mentoring is: | Practice-focused mentoring is not: |

|---|

Mentors and mentees having a common teaching area | Mentors being randomly assigned |

Mentors coaching, supporting and challenging to improve practice | Criticising ‘weak’ practice |

Mentors modelling good practice, addressing agreed subject content and teaching practices | Just sharing lesson plans or tips garnered over a career |

Using observations and data to focus attention on learner outcomes and encourage reflection | Advice based on only ‘gut instinct’ or personal past experience |

Using information about learner outcomes to enable the mentee to improve teaching effectiveness | Setting goals and finding learning opportunities that are not related to the needs of the learners or mentees |

Mentors supporting the mentee’s wellbeing | Simple, sporadic check-ins on wellbeing |

Regular, scheduled discussions and activities | Impromptu conversations that have no set purpose or structure |

Using multiple mentors, online media or networks to draw on expertise | Always a one-to-one relationship |

Reflection

Where do you see examples of practice-based mentoring in your educational setting?

What are your next steps for enhancing practice-based mentoring in your educational setting?

Teaching evaluations / observations are a highly useful form of evidence of teaching practice and proficiency, with research showing lessons learned about the implementation of observation practices. This includes findings from the large-scale Measures

of Effective Teaching (MET) study undertaken in the USA and funded by the Gates Foundation.

(Note: If your educational setting already uses teaching evaluations you can still read and apply the advice below according to the stage of development and context of your organisation)

1. Understand your context

What do you know about the needs of your students? Teachers? Leaders? Community?

2. Purposely choose a system

Compare each option with your setting’s philosophy and goals. Can you see an appropriate alignment?

3. Proactively establish a shared understanding

Identify and clearly communicate what the tool can and cannot accomplish. Bring all staff together and develop a shared vision of how observation supports quality teaching and learning in your context.

4. Be clear and honest about data

Consider what lessons can be learned from the observational evidence data. What are the areas of strength and challenge? How can this guide professional learning?

5. Commit to agreed protocols

Support developing consistency across classrooms and informing professional learning at the setting, team and teacher level. Allow space for identifying any factors that may have impacted on the observation data to reduce the chances of observers deviating

from agreed protocols.

6. Establish a time commitment

The more times a teacher is observed the more stable an estimate of their practice is developed, so reliable observations take more time. Be clear about the time commitment from the start.

Repeat the observation process several times, so that feedback can be addressed over time and then compared against goals.

7. Be aware of observer effects

The education setting size and the selected observation system will determine how many observers are needed. Remember that 'rater bias' is well documented. The more observers there are, the greater the chance of variability.

Provide training on the instrument prior to engaging in any observations.

8. Keep accurate and deliberate records

Record relevant factors such as time of year, activity, discipline area, class size, or other contextual influences. Encourage staff to record and monitor their own reflections.

9. Clarify the role of feedback

Be clear about the role of feedback: teachers need to hear more than ‘you are doing a good job, keep it up’. They require a balance of support and challenge to improve their practice over time.

Encourage specific improvement focused feedback at the same time as recognising and reinforcing teachers’ strengths.

Assist teachers to reflect on feedback collected and to understand the impact of their behaviours. This enables teachers to have greater insight into the relationship between their goals for student learning and their current practice.

10. Be informed

Explore how the Classroom Continuum can support your observation system. Consult research and case studies to assist

in informing choices and practice.

Professional conversation

Connect with a colleague and consider the questions below:

Which of the ten lessons are evident in my context?

Using these ten lessons as a guide, where can we improve the implementation of observation practices?

Leaders can support teachers to develop their practice and increase their impact by ensuring the evidence used in performance and development programs is targeted and relevant.

Reflection for teachers

Does the evidence you collect relate directly to your professional goals?

Is your evidence stored in a logical and easily accessible way?

What does the evidence say about your practice in relation to the Standards?

Reflection for leaders

Are teachers confident in their understanding how to collect the most relevant evidence?

Does your education setting have organised and central evidence storage systems?

How does your educational setting use evidence to evaluate practice in relation to the Standards?

For leaders

For leaders

Return to the